Today I will critique the idea, popularized in the Renaissance, that Gothic buildings like Strasbourg Cathedral, seen at left, are chaotic and disorderly and that architectural harmony depends on the use of the classical orders, seen at right as shown by Serlio. Mine might seem like an unnecessary project, since the Gothic tradition has had many champions in the intervening centuries, but it’s my sense that this myth of Gothic disorderliness continues to shape the writing of art history even today, contributing among other things to the vexed position of architecture in discussions of the Northern Renaissance. Although I am speaking in broad terms about the Gothic and Renaissance design traditions, I recognize the fuzziness and permeability of such categories. I use these terms not only because I find them genuinely helpful in trying to grapple with the complex patterns of European architectural production, but also because this basic framing has figured so prominently in the historiography of the period. For sake of clarity, I will briefly outline my theses before going on to consider that historiography and its consequences.

Today I will critique the idea, popularized in the Renaissance, that Gothic buildings like Strasbourg Cathedral, seen at left, are chaotic and disorderly and that architectural harmony depends on the use of the classical orders, seen at right as shown by Serlio. Mine might seem like an unnecessary project, since the Gothic tradition has had many champions in the intervening centuries, but it’s my sense that this myth of Gothic disorderliness continues to shape the writing of art history even today, contributing among other things to the vexed position of architecture in discussions of the Northern Renaissance. Although I am speaking in broad terms about the Gothic and Renaissance design traditions, I recognize the fuzziness and permeability of such categories. I use these terms not only because I find them genuinely helpful in trying to grapple with the complex patterns of European architectural production, but also because this basic framing has figured so prominently in the historiography of the period. For sake of clarity, I will briefly outline my theses before going on to consider that historiography and its consequences. First, I will argue that the Renaissance dismissal of Gothic architectural order was meant both to encourage and to naturalize the demise this non-classical mode.

First, I will argue that the Renaissance dismissal of Gothic architectural order was meant both to encourage and to naturalize the demise this non-classical mode. Second, I will show that this dismissal was unfair, drawing on some of my own recent geometrical research to demonstrate the procedural logic of Gothic design.

Second, I will show that this dismissal was unfair, drawing on some of my own recent geometrical research to demonstrate the procedural logic of Gothic design. Third, I will argue on this basis that the transition between Gothic and Renaissance design seen across Europe in the sixteenth century had less to do with the taste for order than it did with the taste for Roman-style glory, and what Tom Dandelet has recently called “The Renaissance of Empire.”

Third, I will argue on this basis that the transition between Gothic and Renaissance design seen across Europe in the sixteenth century had less to do with the taste for order than it did with the taste for Roman-style glory, and what Tom Dandelet has recently called “The Renaissance of Empire.” Finally, I will suggest that considerations of local and national pride have played some role in obscuring the dynamics of this broad phenomenon.

Finally, I will suggest that considerations of local and national pride have played some role in obscuring the dynamics of this broad phenomenon. The idea of an opposition between Gothic and Renaissance modes appears already in the middle of the fifteenth century, as when Filarete urged his patron Francesco Sforza to abandon what he called the modo moderno and embrace the modo antico. For Filarete, who was then working in Milan, a conspicuous example of the former mode was the cathedral of Milan.

The idea of an opposition between Gothic and Renaissance modes appears already in the middle of the fifteenth century, as when Filarete urged his patron Francesco Sforza to abandon what he called the modo moderno and embrace the modo antico. For Filarete, who was then working in Milan, a conspicuous example of the former mode was the cathedral of Milan. As Berthold Hub has observed, Filarete’s own designs for structures such as the proposed tower of Sforzinda, at right, are not conventionally classical, and they suggest reference to an antiquity more generalized than that of the Roman Empire alone, but Filarete nevertheless insisted in his text on the superiority of antique models over the supposedly barbaric modern mode that we now call Gothic.

As Berthold Hub has observed, Filarete’s own designs for structures such as the proposed tower of Sforzinda, at right, are not conventionally classical, and they suggest reference to an antiquity more generalized than that of the Roman Empire alone, but Filarete nevertheless insisted in his text on the superiority of antique models over the supposedly barbaric modern mode that we now call Gothic. As a counterpoint of sorts to this attitude, Cesariano half a century later used a modified cross section of Milan cathedral as an exemplar of geometrical order in his 1521 edition of Vitruvius.

As a counterpoint of sorts to this attitude, Cesariano half a century later used a modified cross section of Milan cathedral as an exemplar of geometrical order in his 1521 edition of Vitruvius. His other illustrations, though, contributed to spreading knowledge of classical architecture, and of the orders in particular.

His other illustrations, though, contributed to spreading knowledge of classical architecture, and of the orders in particular. The publication of Serlio’s Libri starting in 1537 contributed even more strongly to this phenomenon, so that the formerly “modern” Gothic style began to seem old-fashioned.

The publication of Serlio’s Libri starting in 1537 contributed even more strongly to this phenomenon, so that the formerly “modern” Gothic style began to seem old-fashioned. Vasari, in the introduction to his Vite, famously criticized what he called the “maniera tedesca” as monstrous, barbarous, and disorderly, or, to use the words quoted in my talk title, “dimenticando ogni lor cosa di ordine.” As Annemarie Sankovitch observed, Vasari’s “maniera tedesca” cannot be directly equated with what we now call the Gothic style, in part because its definition seems to evolve even between the 1550 and 1568 editions of the Vite. In broad terms, however, Vasari was critiquing medieval buildings including Milan cathedral.

Vasari, in the introduction to his Vite, famously criticized what he called the “maniera tedesca” as monstrous, barbarous, and disorderly, or, to use the words quoted in my talk title, “dimenticando ogni lor cosa di ordine.” As Annemarie Sankovitch observed, Vasari’s “maniera tedesca” cannot be directly equated with what we now call the Gothic style, in part because its definition seems to evolve even between the 1550 and 1568 editions of the Vite. In broad terms, however, Vasari was critiquing medieval buildings including Milan cathedral. At times, he seems to have had in mind structures like the façade of Orvieto cathedral, since he laments the use of twisted columns, slender shafts and tall gables that seem thin and insubstantial, like paper. Although Vasari condemns the maniera tedesca as disorderly, he at least engages with architecture, as he basically had to given the importance of builders like Brunelleschi and Bramante in the larger narrative of artistic rebirth that he was aiming to construct.

At times, he seems to have had in mind structures like the façade of Orvieto cathedral, since he laments the use of twisted columns, slender shafts and tall gables that seem thin and insubstantial, like paper. Although Vasari condemns the maniera tedesca as disorderly, he at least engages with architecture, as he basically had to given the importance of builders like Brunelleschi and Bramante in the larger narrative of artistic rebirth that he was aiming to construct. North of the Alps, however, authors such as Domenicus Lampsonius were beginning to construct a canon of northern painters who could be celebrated for their realism, while leaving architecture entirely out of the picture.

North of the Alps, however, authors such as Domenicus Lampsonius were beginning to construct a canon of northern painters who could be celebrated for their realism, while leaving architecture entirely out of the picture. Karel Van Mander took the same basic approach in his Schilderboek, published in 1604, even though he cast his geographical, chronological, and thematic net far more widely, discussing northern painters and printmakers alongside their Italian colleagues and ancient predecessors.

Karel Van Mander took the same basic approach in his Schilderboek, published in 1604, even though he cast his geographical, chronological, and thematic net far more widely, discussing northern painters and printmakers alongside their Italian colleagues and ancient predecessors. In this way Van Mander passed over the awkward fact that heroic fifteenth-century figures like Jan van Eyck lived in an architectural environment that remained Gothic. This approach still dominates discussion of the so-called Northern Renaissance, leaving the history of late Gothic architecture lamentably understudied by comparison.

In this way Van Mander passed over the awkward fact that heroic fifteenth-century figures like Jan van Eyck lived in an architectural environment that remained Gothic. This approach still dominates discussion of the so-called Northern Renaissance, leaving the history of late Gothic architecture lamentably understudied by comparison. In the meanwhile, Gothic architecture received plenty of praise, but even the favorable attention often associated these buildings with the dark, mysterious, and spiritual, in contrast to the lucid rationality of the classical tradition, broadly construed, as this painting by Thomas Cole reminds us.

In the meanwhile, Gothic architecture received plenty of praise, but even the favorable attention often associated these buildings with the dark, mysterious, and spiritual, in contrast to the lucid rationality of the classical tradition, broadly construed, as this painting by Thomas Cole reminds us. In the nineteenth century, of course, scholars such as Viollet-le-Duc celebrated Gothic architecture for its structural and geometrical rationalism. Viollet’s cross-section of Bourges Cathedral at right, however, was inaccurate, and it does little justice to the design’s elegance, as I will show in few minutes.

In the nineteenth century, of course, scholars such as Viollet-le-Duc celebrated Gothic architecture for its structural and geometrical rationalism. Viollet’s cross-section of Bourges Cathedral at right, however, was inaccurate, and it does little justice to the design’s elegance, as I will show in few minutes. Like many of his countrymen, Viollet-le-Duc prioritized the earlier phases of Gothic over the later ones. He dismissed the Strasbourg spire for its supposedly disgraceful silhouette, for example, preferring the simpler forms of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Despite his advocacy of Gothic, therefore, Viollet-le-Duc helped to spread the idea that the Gothic architectural tradition became decadent. It’s that stubbornly persistent idea that I’m now seeking to challenge, while swimming against some powerful historiographical currents.

Like many of his countrymen, Viollet-le-Duc prioritized the earlier phases of Gothic over the later ones. He dismissed the Strasbourg spire for its supposedly disgraceful silhouette, for example, preferring the simpler forms of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Despite his advocacy of Gothic, therefore, Viollet-le-Duc helped to spread the idea that the Gothic architectural tradition became decadent. It’s that stubbornly persistent idea that I’m now seeking to challenge, while swimming against some powerful historiographical currents. The whole of late medieval civilization, for instance, has been widely seen as waning ever since the publication of Johan Huizinga’s “Autumn of the Middle Ages” in 1919.

The whole of late medieval civilization, for instance, has been widely seen as waning ever since the publication of Johan Huizinga’s “Autumn of the Middle Ages” in 1919. Huizinga was more concerned with fifteenth-century painting and literature than with architecture, but his arguments have colored many scholarly perceptions of the period.

Huizinga was more concerned with fifteenth-century painting and literature than with architecture, but his arguments have colored many scholarly perceptions of the period. Henri Focillon, for example, described late Gothic architecture as a phase of decline and decrepitude, comparable to the senescence of an individual. This approach naturalizes the demise of the Gothic tradition in a way that I see as profoundly misleading.

Henri Focillon, for example, described late Gothic architecture as a phase of decline and decrepitude, comparable to the senescence of an individual. This approach naturalizes the demise of the Gothic tradition in a way that I see as profoundly misleading. Meanwhile, many twentieth-century authors discussing figural art of the corresponding years invoked the same basic Northern Renaissance framing pioneered by Lampsonius and Van Mander, as was the case with Max Friedländer.

Meanwhile, many twentieth-century authors discussing figural art of the corresponding years invoked the same basic Northern Renaissance framing pioneered by Lampsonius and Van Mander, as was the case with Max Friedländer. In a similar vein, Erwin Panofsky treated van Eyck within the frame of “Early Netherlandish Painting,” thus rescuing him from the sinking ship of late medievalism.

In a similar vein, Erwin Panofsky treated van Eyck within the frame of “Early Netherlandish Painting,” thus rescuing him from the sinking ship of late medievalism. This emphasis on a conveniently architecture-free Northern Renaissance remains influential even today, especially in the English-speaking world, thanks to the popularity of textbooks like Snyder’s.

This emphasis on a conveniently architecture-free Northern Renaissance remains influential even today, especially in the English-speaking world, thanks to the popularity of textbooks like Snyder’s. This framing obscures the distinction between realistic art made by artists like van Eyck who still lived in a Gothic world, and those like Jan Gossaert, who helped to promote the rise of classical design. The dynamics of the Gothic-to-Renaissance transition thus remain surprisingly understudied, even though the distinction between these two modes has often been remarked.

This framing obscures the distinction between realistic art made by artists like van Eyck who still lived in a Gothic world, and those like Jan Gossaert, who helped to promote the rise of classical design. The dynamics of the Gothic-to-Renaissance transition thus remain surprisingly understudied, even though the distinction between these two modes has often been remarked. This distinction was underscored by two widely cited publications from 1949. James Ackerman’s article “Ars sine scientia nihil est” revealed a rather chaotic ad hoc planning process at the cathedral of Milan around 1400, while Rudolph Wittkower’s book “Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism” argued that Renaissance structures such as Alberti’s façade for Santa Maria Novella in Florence were governed by rigorous proportional relationships comparable to the harmonies of music. Taken at face value, these results make Gothic architecture appear chaotic and unsophisticated compared to that of the emergent Renaissance. In fact, however, the evidence for proportional harmonies in Renaissance design is weaker than Wittkower proposed, and the geometrical rigor of Gothic design was often far greater than most scholars have assumed, as I will now briefly show.

This distinction was underscored by two widely cited publications from 1949. James Ackerman’s article “Ars sine scientia nihil est” revealed a rather chaotic ad hoc planning process at the cathedral of Milan around 1400, while Rudolph Wittkower’s book “Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism” argued that Renaissance structures such as Alberti’s façade for Santa Maria Novella in Florence were governed by rigorous proportional relationships comparable to the harmonies of music. Taken at face value, these results make Gothic architecture appear chaotic and unsophisticated compared to that of the emergent Renaissance. In fact, however, the evidence for proportional harmonies in Renaissance design is weaker than Wittkower proposed, and the geometrical rigor of Gothic design was often far greater than most scholars have assumed, as I will now briefly show. At left, for instance, is a schematic plan of Reims Cathedral, designed soon after 1200, based on a laser survey that I undertook this past summer with my graduate student Rebecca Smith. Building on work by Nancy Wu, Rebecca and I have been able to demonstrate that the whole plan evolves from a series of geometrical steps based on the unfolding of polygons, starting with the decagonal symmetry of the east end, and extending to the square-based forms of the transept and crossing, as seen at right. Gothic designers often created interlocking systems of polygons in elevation, as well.

At left, for instance, is a schematic plan of Reims Cathedral, designed soon after 1200, based on a laser survey that I undertook this past summer with my graduate student Rebecca Smith. Building on work by Nancy Wu, Rebecca and I have been able to demonstrate that the whole plan evolves from a series of geometrical steps based on the unfolding of polygons, starting with the decagonal symmetry of the east end, and extending to the square-based forms of the transept and crossing, as seen at right. Gothic designers often created interlocking systems of polygons in elevation, as well. Here, for instance, is a laser-scanned section of Bourges Cathedral made by Andrew Tallon.

Here, for instance, is a laser-scanned section of Bourges Cathedral made by Andrew Tallon. And here is my analysis of its geometry. As you can see, the total height to the roofline is set by a great square framing the buttresses, while the height to the pinnacle tips is given by an equilateral triangle sharing the square’s baseline. The smaller yellow equilateral triangle whose baseline matches the width between the glass planes in the aisles gives the interior height of the vaults. There are obviously many more details in these schemes that I don’t have time to unpack in today’s short presentation, but I hope the general picture comes through clearly.

And here is my analysis of its geometry. As you can see, the total height to the roofline is set by a great square framing the buttresses, while the height to the pinnacle tips is given by an equilateral triangle sharing the square’s baseline. The smaller yellow equilateral triangle whose baseline matches the width between the glass planes in the aisles gives the interior height of the vaults. There are obviously many more details in these schemes that I don’t have time to unpack in today’s short presentation, but I hope the general picture comes through clearly. Vasari would not have known Reims or Bourges, but some of the same design principles seen at those French buildings also govern the façade at Orvieto.

Vasari would not have known Reims or Bourges, but some of the same design principles seen at those French buildings also govern the façade at Orvieto. The height to the center of the rose, for instance, is set by an equilateral triangle sharing its baseline with a square framing the façade composition. The top of the triforium aligns with the corners of an octagon inscribed within that square.

The height to the center of the rose, for instance, is set by an equilateral triangle sharing its baseline with a square framing the façade composition. The top of the triforium aligns with the corners of an octagon inscribed within that square. A second equilateral triangle based on the corners of a smaller octagon gives the profile of the upper gable.

A second equilateral triangle based on the corners of a smaller octagon gives the profile of the upper gable. The current facade represents a refinement of design themes introduced in two surviving drawings, of which I now show one at right. The analysis of such drawings can give an intimate perspective on the Gothic design process.

The current facade represents a refinement of design themes introduced in two surviving drawings, of which I now show one at right. The analysis of such drawings can give an intimate perspective on the Gothic design process. As a final case, I here show you an overall view and a detail of a remarkable 4-meter high drawing that has only recently come to scholarly attention. Costanza Beltrami has convincingly argued that this is the drawing for the crossing spire of Rouen cathedral, presented by designer Roland le Roux in 1516.

As a final case, I here show you an overall view and a detail of a remarkable 4-meter high drawing that has only recently come to scholarly attention. Costanza Beltrami has convincingly argued that this is the drawing for the crossing spire of Rouen cathedral, presented by designer Roland le Roux in 1516. Although the drawing incorporates pseudo-perspectival depth cues, I found that its proportions derive from a rigorously constructed geometrical armature just like those used for earlier Gothic drawings that present strictly orthogonal views.

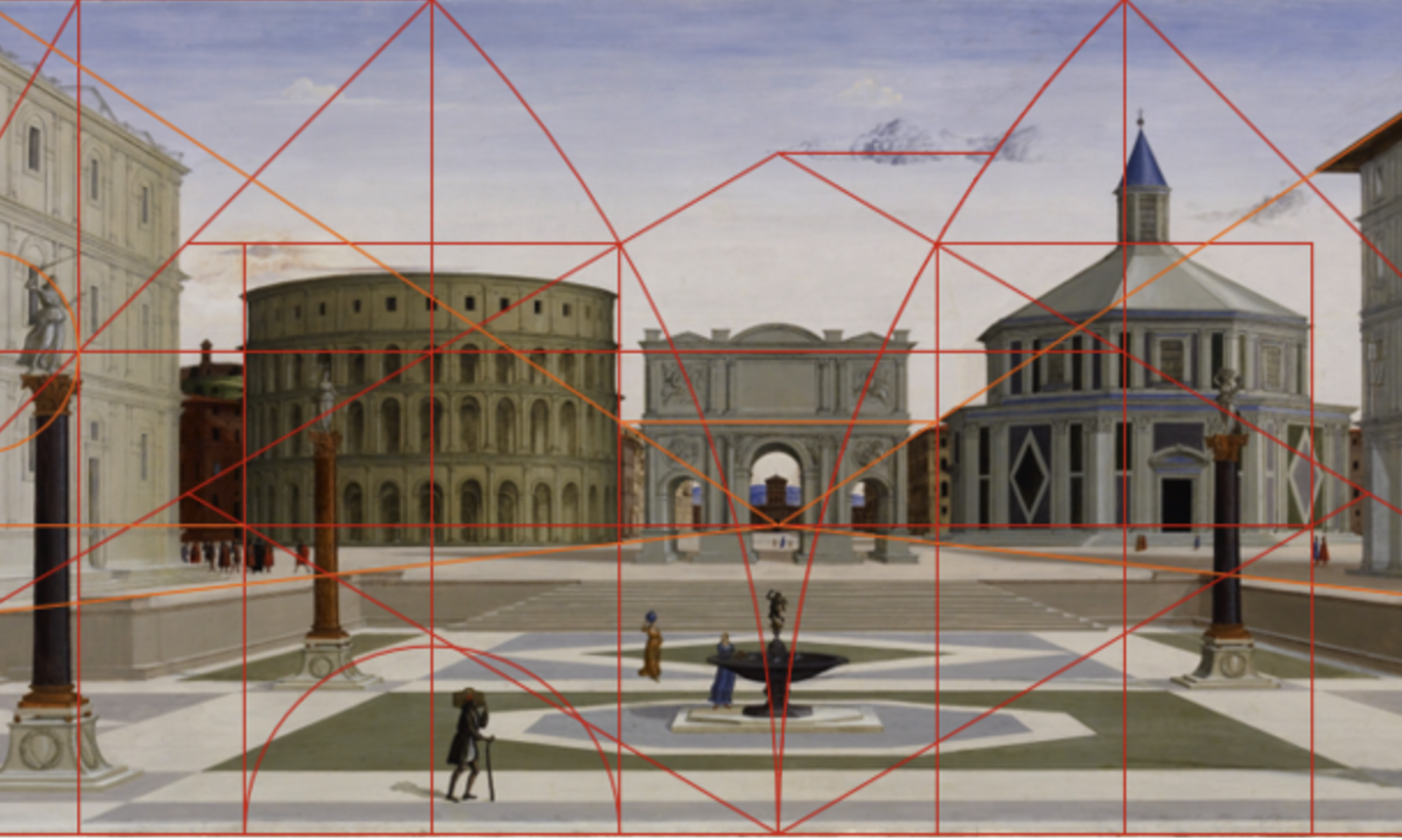

Although the drawing incorporates pseudo-perspectival depth cues, I found that its proportions derive from a rigorously constructed geometrical armature just like those used for earlier Gothic drawings that present strictly orthogonal views. Despite its high degree of geometrical and formal order, the Rouen drawing does not have the clear and lucid appearance of Brunelleschi’s San Lorenzo in Florence, designed nearly a century earlier. This distinction has doubtless contributed to the historiographical trend that I discussed earlier, which I described in my title as the myth of Gothic license. As I have tried to briefly show, Gothic design was, in fact, no more wayward than classical design. In technical terms, moreover, guild-trained Gothic builders were at least as competent as most of the goldsmiths, sculptors, and painters who began to get building commissions in the Renaissance, although I recognize Brunelleschi as an exception to that rule. Since Renaissance buildings were neither more orderly nor more robust than Gothic buildings, the diffusion of antique design must have been motivated by other factors. Of these, I see political symbolism as by far the most important. Although the Renaissance manner first emerged in Republican Florence, its spread was tied up more with imperial than with republican ideals. Even in Florence, the Medici were emerging as a quasi-princely family already in the fifteenth century, and their patronage of San Lorenzo expressed their family’s dignity as much or more than the city’s. As Tom Dandelet has noted in his recent book “The Renaissance of Empire,” classicizing buildings became fashionable throughout Europe largely because of their usefulness in princely propaganda.

Despite its high degree of geometrical and formal order, the Rouen drawing does not have the clear and lucid appearance of Brunelleschi’s San Lorenzo in Florence, designed nearly a century earlier. This distinction has doubtless contributed to the historiographical trend that I discussed earlier, which I described in my title as the myth of Gothic license. As I have tried to briefly show, Gothic design was, in fact, no more wayward than classical design. In technical terms, moreover, guild-trained Gothic builders were at least as competent as most of the goldsmiths, sculptors, and painters who began to get building commissions in the Renaissance, although I recognize Brunelleschi as an exception to that rule. Since Renaissance buildings were neither more orderly nor more robust than Gothic buildings, the diffusion of antique design must have been motivated by other factors. Of these, I see political symbolism as by far the most important. Although the Renaissance manner first emerged in Republican Florence, its spread was tied up more with imperial than with republican ideals. Even in Florence, the Medici were emerging as a quasi-princely family already in the fifteenth century, and their patronage of San Lorenzo expressed their family’s dignity as much or more than the city’s. As Tom Dandelet has noted in his recent book “The Renaissance of Empire,” classicizing buildings became fashionable throughout Europe largely because of their usefulness in princely propaganda. One of the first major classicizing structures built outside of Florence, for instance, was the triumphal arch wedged between the towers of the Castel Nuovo in Naples in the mid-fifteenth century.

One of the first major classicizing structures built outside of Florence, for instance, was the triumphal arch wedged between the towers of the Castel Nuovo in Naples in the mid-fifteenth century. Its construction celebrated the victory of King Alfonso V, who conquered the city in 1442.

Its construction celebrated the victory of King Alfonso V, who conquered the city in 1442. Three decades later Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, whose kingdom had deep bonds with Naples, became one of the first major patrons of the antique mode north of the Alps.

Three decades later Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, whose kingdom had deep bonds with Naples, became one of the first major patrons of the antique mode north of the Alps. His great library would eventually house fine Italian books, including this manuscript of Filarete’s architectural treatise. Interestingly, however, he acquired this book only years after he had begun to hire Italian craftsmen to add classical articulation to his palace in Buda.

His great library would eventually house fine Italian books, including this manuscript of Filarete’s architectural treatise. Interestingly, however, he acquired this book only years after he had begun to hire Italian craftsmen to add classical articulation to his palace in Buda. This initiative involved the addition of literal window dressing and fixtures like this impressive red marble frame, rather than a deep rethinking of the palace’s structure and proportions. These facts strongly suggest that it was the imperial association of the antique mode, more than theoretical, structural, or even aesthetic concerns, that appealed most to the king, who continued to sponsor the construction of Gothic churches down to the end of his reign. Another major factor in the spread of antique design was its association with the papacy.

This initiative involved the addition of literal window dressing and fixtures like this impressive red marble frame, rather than a deep rethinking of the palace’s structure and proportions. These facts strongly suggest that it was the imperial association of the antique mode, more than theoretical, structural, or even aesthetic concerns, that appealed most to the king, who continued to sponsor the construction of Gothic churches down to the end of his reign. Another major factor in the spread of antique design was its association with the papacy. Renaissance popes such as Julius II used the construction of classicizing buildings to express the idea of papal Rome as the triumphant Christian successor of imperial Rome.

Renaissance popes such as Julius II used the construction of classicizing buildings to express the idea of papal Rome as the triumphant Christian successor of imperial Rome. In seeking a designer for his grandiose rebuilding of Saint Peter’s basilica, Julius famously turned to Bramante, who had designed the compact but handsome Tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio for Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain in the years just after 1500.

In seeking a designer for his grandiose rebuilding of Saint Peter’s basilica, Julius famously turned to Bramante, who had designed the compact but handsome Tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio for Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain in the years just after 1500. Three decades later their grandson Charles V would sponsor the construction of a strongly Bramantesque imperial palace in the midst of Granada’s Alhambra. By the mid-sixteenth century, he and his Habsburg siblings would rank among the most important patrons of classicizing building projects across Europe.

Three decades later their grandson Charles V would sponsor the construction of a strongly Bramantesque imperial palace in the midst of Granada’s Alhambra. By the mid-sixteenth century, he and his Habsburg siblings would rank among the most important patrons of classicizing building projects across Europe. The French monarchy also contributed to this trend. Charles VIII, for instance, brought Italian artists and builders back to France after he invaded Italy in 1494 to press his claim to the kingdom of Naples. His successors Louis XII and Francis I followed his example both in invading Italy and in recruiting Italians to their courts.

The French monarchy also contributed to this trend. Charles VIII, for instance, brought Italian artists and builders back to France after he invaded Italy in 1494 to press his claim to the kingdom of Naples. His successors Louis XII and Francis I followed his example both in invading Italy and in recruiting Italians to their courts. Francis I thus hired Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio to decorate his chateau at Fontainebleau. These royal initiatives, and others that I do not have time even to mention in today’s short talk, played a crucial role in establishing Italianate Renaissance classicism as the stylistic mode of choice for elite patrons all across Europe. As a fan of Gothic architecture, I see this development as less than wholly positive. I also find it ironic that the pursuit of quasi-imperial glory would lead so many rulers to embrace the Italianate classical mode at the expense of their countries’ own native Gothic traditions, whose value in expressing national identity would be recovered and celebrated in the nineteenth century. This tension between national traditions and international trends continues to shape discourse on this period even today.

Francis I thus hired Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio to decorate his chateau at Fontainebleau. These royal initiatives, and others that I do not have time even to mention in today’s short talk, played a crucial role in establishing Italianate Renaissance classicism as the stylistic mode of choice for elite patrons all across Europe. As a fan of Gothic architecture, I see this development as less than wholly positive. I also find it ironic that the pursuit of quasi-imperial glory would lead so many rulers to embrace the Italianate classical mode at the expense of their countries’ own native Gothic traditions, whose value in expressing national identity would be recovered and celebrated in the nineteenth century. This tension between national traditions and international trends continues to shape discourse on this period even today. Francis I thus hired Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio to decorate his chateau at Fontainebleau. These royal initiatives, and others that I do not have time even to mention in today’s short talk, played a crucial role in establishing Italianate Renaissance classicism as the stylistic mode of choice for elite patrons all across Europe. As a fan of Gothic architecture, I see this development as less than wholly positive. I also find it ironic that the pursuit of quasi-imperial glory would lead so many rulers to embrace the Italianate classical mode at the expense of their countries’ own native Gothic traditions, whose value in expressing national identity would be recovered and celebrated in the nineteenth century. This tension between national traditions and international trends continues to shape discourse on this period even today.

Francis I thus hired Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio to decorate his chateau at Fontainebleau. These royal initiatives, and others that I do not have time even to mention in today’s short talk, played a crucial role in establishing Italianate Renaissance classicism as the stylistic mode of choice for elite patrons all across Europe. As a fan of Gothic architecture, I see this development as less than wholly positive. I also find it ironic that the pursuit of quasi-imperial glory would lead so many rulers to embrace the Italianate classical mode at the expense of their countries’ own native Gothic traditions, whose value in expressing national identity would be recovered and celebrated in the nineteenth century. This tension between national traditions and international trends continues to shape discourse on this period even today. First, the myth of Gothic license, which naturalizes the demise of the Gothic mode. Second, the traditional framing of the Northern Renaissance, which leaves the pivot from Gothic to classical design almost entirely out of the picture. And third, the tendency to elide the distinctions between these architectural cultures as if the transition between them did not matter. As I’ve said, though, I recognize that there was never a clear bright line between medieval and Renaissance building practice, a lesson that I’ve learned in part through dialog with Matt Cohen. Without further ado, therefore, I will conclude here, so that we can get Matt’s rather different perspective on the relationship between medieval and Renaissance design.

First, the myth of Gothic license, which naturalizes the demise of the Gothic mode. Second, the traditional framing of the Northern Renaissance, which leaves the pivot from Gothic to classical design almost entirely out of the picture. And third, the tendency to elide the distinctions between these architectural cultures as if the transition between them did not matter. As I’ve said, though, I recognize that there was never a clear bright line between medieval and Renaissance building practice, a lesson that I’ve learned in part through dialog with Matt Cohen. Without further ado, therefore, I will conclude here, so that we can get Matt’s rather different perspective on the relationship between medieval and Renaissance design.