Here is Masaccio’s Trinity.

Here is Masaccio’s Trinity. It makes sense to begin this analysis with consideration of the most prominent circle in the composition, the exterior margin of the arch framing the barrel-vaulted chapel. The vertical tangents to this circle are the interior margins of the large, fluted pilasters framing the composition. If one draws a square within the circle framed by these verticals, one finds that its edges are tangent to the corners of the abaci supporting the main arch. Also, is one draws a larger circle around the square framing the original circle, one finds the margins of the whole composition.

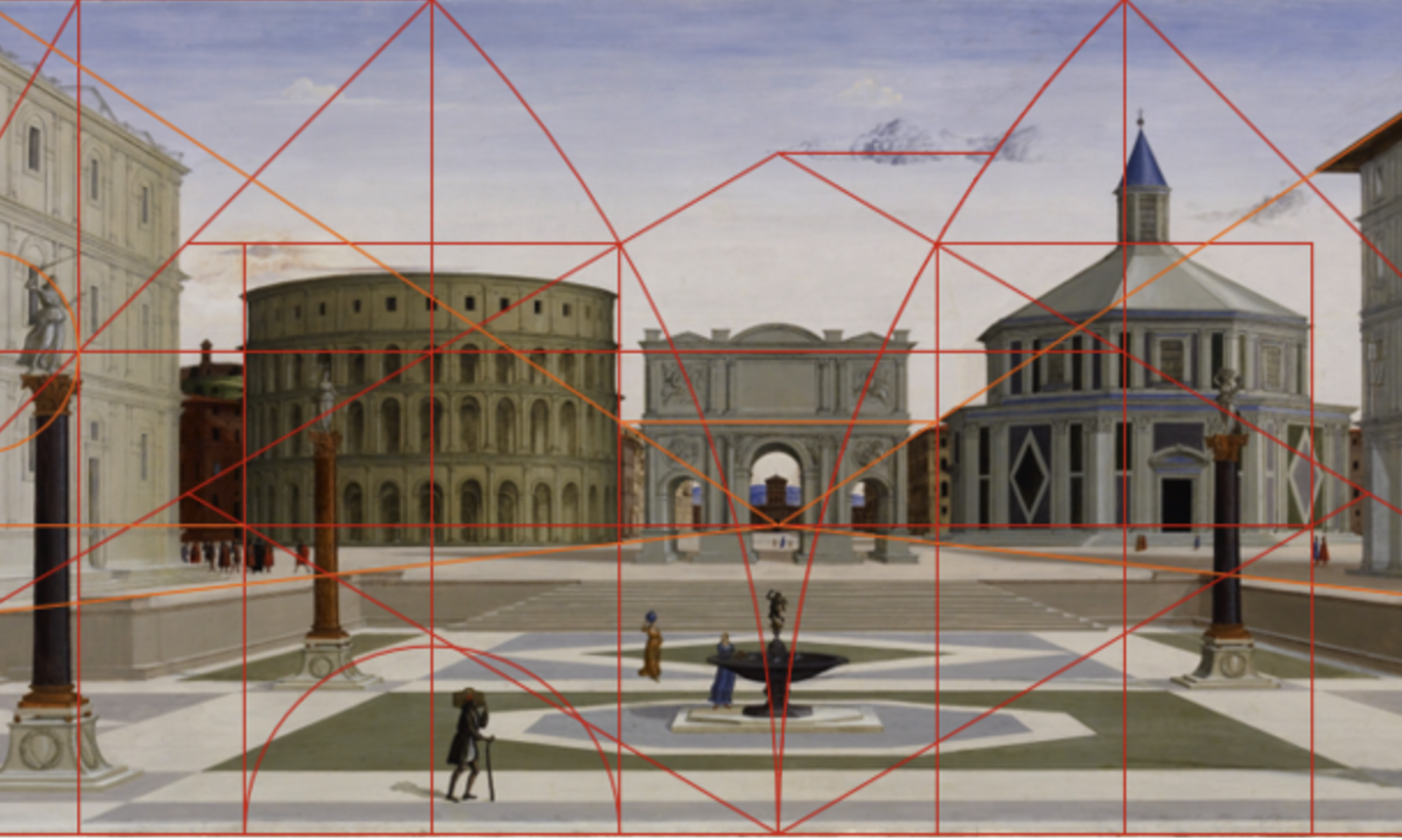

It makes sense to begin this analysis with consideration of the most prominent circle in the composition, the exterior margin of the arch framing the barrel-vaulted chapel. The vertical tangents to this circle are the interior margins of the large, fluted pilasters framing the composition. If one draws a square within the circle framed by these verticals, one finds that its edges are tangent to the corners of the abaci supporting the main arch. Also, is one draws a larger circle around the square framing the original circle, one finds the margins of the whole composition. Around the large red circle just described, circumscribe an octagon. The horizontal connecting the top points of its lateral facets establishes the top of the fluted pilaster shafts. The corresponding horizontal connecting the bottom points of its lateral facets passes through the stigmata in Christ’s hands, and between His eyes. When an equivalent octagon is constructed in the lower half of the composition, one finds that the upper horizontal aligns with the patrons’ praying hands, and that the lower defines the top edge of the recessed niche in the tomb below. Crucially, too, the outer edge of the fluted pilasters are verticals passing through the points where the rays connecting the center of the upper octagon to its corners intersect the large red circle filling the top half of the composition.

Around the large red circle just described, circumscribe an octagon. The horizontal connecting the top points of its lateral facets establishes the top of the fluted pilaster shafts. The corresponding horizontal connecting the bottom points of its lateral facets passes through the stigmata in Christ’s hands, and between His eyes. When an equivalent octagon is constructed in the lower half of the composition, one finds that the upper horizontal aligns with the patrons’ praying hands, and that the lower defines the top edge of the recessed niche in the tomb below. Crucially, too, the outer edge of the fluted pilasters are verticals passing through the points where the rays connecting the center of the upper octagon to its corners intersect the large red circle filling the top half of the composition. The top edge of the lintel over the main arch passes through points where the diagonals of the original large circle pass through verticals ¾ of the way through the pilasters, as the yellow triangular constructions in their capitals indicate. Below, the chins of the Virgin and Saint John align with the upper facet of a yellow octagon framed by the outer pilaster margins. The lower edge of the lintel on which the patrons knee corresponds to a horizontal drawn through the points where the rays of the lower octagon intersect the red verticals defining the inner edge of the pilasters. The skeleton, similarly, rests on a horizontal drawn through the points where the diagonal facets of this octagon intersect these verticals.

The top edge of the lintel over the main arch passes through points where the diagonals of the original large circle pass through verticals ¾ of the way through the pilasters, as the yellow triangular constructions in their capitals indicate. Below, the chins of the Virgin and Saint John align with the upper facet of a yellow octagon framed by the outer pilaster margins. The lower edge of the lintel on which the patrons knee corresponds to a horizontal drawn through the points where the rays of the lower octagon intersect the red verticals defining the inner edge of the pilasters. The skeleton, similarly, rests on a horizontal drawn through the points where the diagonal facets of this octagon intersect these verticals. The axes of the large round columns are found halfway between the red verticals tangent to their capital abaci, on the inside, and the green verticals ¼ of the way through the pilasters, on the outside. The tops of the abaci, of course, align with the equator of the original big circle. The bottom-most horizontal in the composition, finally, passes through points where extensions of the lower diagonal octagon facets intersect lines of 30-degree slope descending from the midpoint of its bottom facet.

The axes of the large round columns are found halfway between the red verticals tangent to their capital abaci, on the inside, and the green verticals ¼ of the way through the pilasters, on the outside. The tops of the abaci, of course, align with the equator of the original big circle. The bottom-most horizontal in the composition, finally, passes through points where extensions of the lower diagonal octagon facets intersect lines of 30-degree slope descending from the midpoint of its bottom facet. Near the top of the composition, a major horizontal in the entablature can be found half a pilaster width above the upper edge of the main lintel, as the small triangular constructions at upper left and upper right show. More importantly, the inner margins of the columns can be found by drawing vertical tangents to the circles describing their cross-sections, whose radii equal the distance between the pilasters and the column axes (this construction works more precisely at left than at right, as will be true of some other details, as well). The lower lip of the main arch corresponds fairly closely to the semicircle framed by the column margins, but there are some deviations there, likely to prepare the way for the notionally perspectival treatment of the arch’s lower surface and the barrel vault behind it.

Near the top of the composition, a major horizontal in the entablature can be found half a pilaster width above the upper edge of the main lintel, as the small triangular constructions at upper left and upper right show. More importantly, the inner margins of the columns can be found by drawing vertical tangents to the circles describing their cross-sections, whose radii equal the distance between the pilasters and the column axes (this construction works more precisely at left than at right, as will be true of some other details, as well). The lower lip of the main arch corresponds fairly closely to the semicircle framed by the column margins, but there are some deviations there, likely to prepare the way for the notionally perspectival treatment of the arch’s lower surface and the barrel vault behind it. The prominent horizontal just behind Christ’s hips passes through the points where the column margins intersect the diagonal facets of the large upper octagon. The top edge of the ledge where the cross stands, the top edge of the ledge where the patrons kneel, and the top edge of the molding on the front of that ledge can all be found by bouncing diagonals upward within the vertical strip defined by the column, taking the previously defined yellow horizontal as a baseline. The bases of the slender twin columns supporting these ledges, finally, can be found by drawing a horizontal tangent to the lower arc of the circle circumscribing the large lower octagon.

The prominent horizontal just behind Christ’s hips passes through the points where the column margins intersect the diagonal facets of the large upper octagon. The top edge of the ledge where the cross stands, the top edge of the ledge where the patrons kneel, and the top edge of the molding on the front of that ledge can all be found by bouncing diagonals upward within the vertical strip defined by the column, taking the previously defined yellow horizontal as a baseline. The bases of the slender twin columns supporting these ledges, finally, can be found by drawing a horizontal tangent to the lower arc of the circle circumscribing the large lower octagon. The arch describing the back wall of the vaulted chapel space can be described by a circle framed by the red square inscribed within the original red circle framing the front arch; it is thus smaller than front circle by a factor of root two. The midpoint of this circle is located one half a column-radius above the bottom of that original red circle; this level also corresponds to the top edge of the abaci on the rear columns.

The arch describing the back wall of the vaulted chapel space can be described by a circle framed by the red square inscribed within the original red circle framing the front arch; it is thus smaller than front circle by a factor of root two. The midpoint of this circle is located one half a column-radius above the bottom of that original red circle; this level also corresponds to the top edge of the abaci on the rear columns. The corners of the rear abaci align with white verticals whose upper points mark the intersections between diagonals of the original red circle and diagonals of the new violet circle. The supposedly perspectival orthogonals describing the lateral edges of the abaci can then be drawn in, converging at a point just below the center of the lower octagon. The interections of these “orthogonals” with the blue horizontal through Christ’s hips mark points through which other verticals articulating the back wall of the chapel can be drawn. These steps show that Masaccio’s Trinity, like most paintings of its era, was composed largely in terms of plane geometry, its innovative perspectival rendering notwithstanding.

The corners of the rear abaci align with white verticals whose upper points mark the intersections between diagonals of the original red circle and diagonals of the new violet circle. The supposedly perspectival orthogonals describing the lateral edges of the abaci can then be drawn in, converging at a point just below the center of the lower octagon. The interections of these “orthogonals” with the blue horizontal through Christ’s hips mark points through which other verticals articulating the back wall of the chapel can be drawn. These steps show that Masaccio’s Trinity, like most paintings of its era, was composed largely in terms of plane geometry, its innovative perspectival rendering notwithstanding.