Based on a CAA presentation given in 2008 by Robert Bork

Evolutionism has something of a bad reputation in art-historical circles. Since Gombrich claimed half a century ago that evolutionism was dead, it would be easy to assume that art history has nothing more to learn from the work of Charles Darwin.

Evolutionism has something of a bad reputation in art-historical circles. Since Gombrich claimed half a century ago that evolutionism was dead, it would be easy to assume that art history has nothing more to learn from the work of Charles Darwin. But I will argue today that engagement with Darwin’s legacy can benefit art history on a variety of levels. I will claim, in fact, that Darwinian evolutionary theory provides a framework for understanding formal change over time that incorporates many of the profound insights achieved by art historians such as: Alois Riegl, Heinrich Wölfflin, and Gombrich himself.

But I will argue today that engagement with Darwin’s legacy can benefit art history on a variety of levels. I will claim, in fact, that Darwinian evolutionary theory provides a framework for understanding formal change over time that incorporates many of the profound insights achieved by art historians such as: Alois Riegl, Heinrich Wölfflin, and Gombrich himself. To make this case, I will discuss four principal themes. First, I will try to briefly explain what Gombrich meant by evolutionism. Second, I will quickly outline some of the key features of Darwinian evolutionary theory. In the third and longest section of my talk, I will illustrate some of the parallels between patterns of artistic and biological evolution. Such parallels, I will argue, help to demonstrate the intrinsic relevance of Darwinian theory for the practice of art history. Fourth and finally, I will take a broader perspective on the place of our discipline in the modern academy, presenting some extrinsic reasons why it makes sense for art historians to explore Darwinian evolutionary theory.

To make this case, I will discuss four principal themes. First, I will try to briefly explain what Gombrich meant by evolutionism. Second, I will quickly outline some of the key features of Darwinian evolutionary theory. In the third and longest section of my talk, I will illustrate some of the parallels between patterns of artistic and biological evolution. Such parallels, I will argue, help to demonstrate the intrinsic relevance of Darwinian theory for the practice of art history. Fourth and finally, I will take a broader perspective on the place of our discipline in the modern academy, presenting some extrinsic reasons why it makes sense for art historians to explore Darwinian evolutionary theory. To put this argument into context, I should begin by observing that the discipline of art history itself has evolved, spawning a series of distinct theories of diachronic change in visual culture. In a short talk like this one, I can cite only a few examples, and I won’t do justice even to these. I hope, nevertheless, that this discussion can provide a standard against which to judge the power and relevance of Darwinian theory for art history.

To put this argument into context, I should begin by observing that the discipline of art history itself has evolved, spawning a series of distinct theories of diachronic change in visual culture. In a short talk like this one, I can cite only a few examples, and I won’t do justice even to these. I hope, nevertheless, that this discussion can provide a standard against which to judge the power and relevance of Darwinian theory for art history. Giorgio Vasari, who pioneered systematic art-historical writing in the sixteenth century, adopted a simpler biological metaphor, comparing artistic developments to the life cycles of individual organisms. This model of stylistic change, which calls to mind the roughly contemporary painting of the three ages of woman by Hans Baldung Grien at left, has a kind of seductive clarity, but it has many flaws. It is linear, deterministic, and at least implicitly judgmental, suggesting that stylistic movements and cultural epochs have pre-determined lifespans, whose later phases culminate in senescence and death. Echoes of this Vasarian model continued to inform many prominent authors into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Since my own research focuses principally on late Gothic architecture, I have been particularly struck by the ways this attitude has devalued art of the late Middle Ages, which was labeled as decadent by Prosper Merimée and autumnal by Johan Huizinga, whose work on the “Waning of the Middle Ages” remains influential to this day.

Giorgio Vasari, who pioneered systematic art-historical writing in the sixteenth century, adopted a simpler biological metaphor, comparing artistic developments to the life cycles of individual organisms. This model of stylistic change, which calls to mind the roughly contemporary painting of the three ages of woman by Hans Baldung Grien at left, has a kind of seductive clarity, but it has many flaws. It is linear, deterministic, and at least implicitly judgmental, suggesting that stylistic movements and cultural epochs have pre-determined lifespans, whose later phases culminate in senescence and death. Echoes of this Vasarian model continued to inform many prominent authors into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Since my own research focuses principally on late Gothic architecture, I have been particularly struck by the ways this attitude has devalued art of the late Middle Ages, which was labeled as decadent by Prosper Merimée and autumnal by Johan Huizinga, whose work on the “Waning of the Middle Ages” remains influential to this day. An alternative and less judgmental approach to artistic development emerged in the philosophical writings of GWF Hegel, who understood cultural change as a manifestation of the progress of the Zeitgeist, or spirit of the age. Hegel saw the succession from Egyptian to Greek and eventually to Christian art as symptomatic of this progressive development. By reading art history in these teleological terms, he removed the stigma from late stylistic phases, allowing artworks to be interpreted more on their own terms, instead of being measured against fixed standards of beauty.

An alternative and less judgmental approach to artistic development emerged in the philosophical writings of GWF Hegel, who understood cultural change as a manifestation of the progress of the Zeitgeist, or spirit of the age. Hegel saw the succession from Egyptian to Greek and eventually to Christian art as symptomatic of this progressive development. By reading art history in these teleological terms, he removed the stigma from late stylistic phases, allowing artworks to be interpreted more on their own terms, instead of being measured against fixed standards of beauty. Alois Riegl, in his pioneering Stilfragen of 1893, arrived at roughly comparable vision of stylistic development in a far more scholarly fashion, based on the careful examination of formal details such as acanthus scrolls and arabesques. Riegl’s views on artistic change were more nuanced and complex than Hegel’s, and they evolved over time, but the most frequently cited versions of his theory of artistic will, or Kunstwollen, remain linear, deterministic, and Hegelian in flavor, as Inge Lise Mogensen will explain to us shortly. This Hegelian intellectual tradition has little in common with Darwinian evolutionary theory, but the distinctions between the two have often been overlooked.

Alois Riegl, in his pioneering Stilfragen of 1893, arrived at roughly comparable vision of stylistic development in a far more scholarly fashion, based on the careful examination of formal details such as acanthus scrolls and arabesques. Riegl’s views on artistic change were more nuanced and complex than Hegel’s, and they evolved over time, but the most frequently cited versions of his theory of artistic will, or Kunstwollen, remain linear, deterministic, and Hegelian in flavor, as Inge Lise Mogensen will explain to us shortly. This Hegelian intellectual tradition has little in common with Darwinian evolutionary theory, but the distinctions between the two have often been overlooked. In the popular imagination, especially, Darwinian evolution remains generally associated with linear progress, as seen in this recent cartoon version of the classic “ascent of man” diagram. Even within the academy, the term evolution retains these connotations, even though real Darwinian evolutionary models are neither linear nor teleological. This linguistic conflation helps to explain how Gombrich could write, in Art and Illusion, that evolutionism was dead, while affirming in an interview decades later that his work had a somewhat evolutionary flavor. The evolutionism that Gombrich emphatically rejected was the linear determinism of the Heglian tradition. He had far greater sympathy for the scientific tradition from which Darwin’s theory emerged. His nuanced discussion of cultural and artistic development, moreover, can be easily translated into a Darwinian language of cultural evolution.

In the popular imagination, especially, Darwinian evolution remains generally associated with linear progress, as seen in this recent cartoon version of the classic “ascent of man” diagram. Even within the academy, the term evolution retains these connotations, even though real Darwinian evolutionary models are neither linear nor teleological. This linguistic conflation helps to explain how Gombrich could write, in Art and Illusion, that evolutionism was dead, while affirming in an interview decades later that his work had a somewhat evolutionary flavor. The evolutionism that Gombrich emphatically rejected was the linear determinism of the Heglian tradition. He had far greater sympathy for the scientific tradition from which Darwin’s theory emerged. His nuanced discussion of cultural and artistic development, moreover, can be easily translated into a Darwinian language of cultural evolution. Before going on to show how Darwinian evolutionary theory can apply to the history of art, I should briefly outline the fundamentals of Darwin’s theory, so as to distinguish it from the linear determinism with which it is so often confused. The basic engine of change in Darwinian evolution is natural selection, the process by which environmental factors weed out certain members of a given population before they can reproduce.

Before going on to show how Darwinian evolutionary theory can apply to the history of art, I should briefly outline the fundamentals of Darwin’s theory, so as to distinguish it from the linear determinism with which it is so often confused. The basic engine of change in Darwinian evolution is natural selection, the process by which environmental factors weed out certain members of a given population before they can reproduce. In the nineteenth century, for example, the widespread burning of coal blackened many forests in England, which meant that birds could find and devour white pepper moths more easily than their darker and better-camouflaged cousins. Over the course of a few decades, therefore, the color balance within the pepper moth population shifted decidedly to the darker side. Highly specific selection pressures like this one, significantly, can alter not just the percentage of old forms; it can actually drive the development of wholly new forms.

In the nineteenth century, for example, the widespread burning of coal blackened many forests in England, which meant that birds could find and devour white pepper moths more easily than their darker and better-camouflaged cousins. Over the course of a few decades, therefore, the color balance within the pepper moth population shifted decidedly to the darker side. Highly specific selection pressures like this one, significantly, can alter not just the percentage of old forms; it can actually drive the development of wholly new forms. Selective breeding orchestrated by humans has produced many breeds of dogs very different than their wolf-like ancestors. Darwin’s great insight was to realize that natural selection, unguided by human intelligence, could have effects precisely analogous to those he had seen in human-guided-breeding.

Selective breeding orchestrated by humans has produced many breeds of dogs very different than their wolf-like ancestors. Darwin’s great insight was to realize that natural selection, unguided by human intelligence, could have effects precisely analogous to those he had seen in human-guided-breeding. This diagram shows a classic example of how that process works, the evolution of the giraffe’s long neck. In the upper full row, you can see a variety of proto-giraffes, with varying but moderate neck lengths. Since a longer neck allows access to more vegetation, individuals with long necks would tend to survive and reproduce better in times of scarcity. So, you can see that these are the individuals that pass on their genes to the subsequent generation, as the linking lines indicate, while those with shorter necks fail to reproduce, as these black terminal boxes show. The process repeats itself in the lower rows. Over the course of many generations, the average neck length will increase, producing giraffe populations like those we see today. Clearly, this process is neither linear, nor teleological and deterministic. Instead, it involves lots of randomicity and dead ends.

This diagram shows a classic example of how that process works, the evolution of the giraffe’s long neck. In the upper full row, you can see a variety of proto-giraffes, with varying but moderate neck lengths. Since a longer neck allows access to more vegetation, individuals with long necks would tend to survive and reproduce better in times of scarcity. So, you can see that these are the individuals that pass on their genes to the subsequent generation, as the linking lines indicate, while those with shorter necks fail to reproduce, as these black terminal boxes show. The process repeats itself in the lower rows. Over the course of many generations, the average neck length will increase, producing giraffe populations like those we see today. Clearly, this process is neither linear, nor teleological and deterministic. Instead, it involves lots of randomicity and dead ends. One crucial point here is that highly non-random environmental selections factors operate on random variances in the population. It is precisely this interaction between random and non-random factors that makes evolution possible. In art history, analogously, selection pressures determined by the cultural environment can shape the reception of the widely varied new formal ideas generated by artists.

One crucial point here is that highly non-random environmental selections factors operate on random variances in the population. It is precisely this interaction between random and non-random factors that makes evolution possible. In art history, analogously, selection pressures determined by the cultural environment can shape the reception of the widely varied new formal ideas generated by artists. To show what I mean by this analogy, I’d like to briefly discuss some of the patterns of development seen in natural history, starting with some famous examples that were particularly important to the development of Darwin’s own thinking.

To show what I mean by this analogy, I’d like to briefly discuss some of the patterns of development seen in natural history, starting with some famous examples that were particularly important to the development of Darwin’s own thinking. The young Darwin, whose portrait you see at right, took part in an exploratory voyage by the HMS Beagle starting in 1831. In the course of its 5-year mission to seek out new life and new civilizations—a clear inspiration for the mission profile of the starship Enterprise--the ship visited the Galapagos islands, where Darwin collected valuable evidence that would inform his ideas about speciation. The finches of the Galapagos proved particularly influential in this context.

The young Darwin, whose portrait you see at right, took part in an exploratory voyage by the HMS Beagle starting in 1831. In the course of its 5-year mission to seek out new life and new civilizations—a clear inspiration for the mission profile of the starship Enterprise--the ship visited the Galapagos islands, where Darwin collected valuable evidence that would inform his ideas about speciation. The finches of the Galapagos proved particularly influential in this context. Finch beaks, Darwin realized, reflect the principle that Louis Sullivan would later describe by the phrase “form follows function.” Birds that eat large seeds have thick beaks that act like heavy pliers, while those that eat small seeds have sharp beaks like needle-nosed pliers. These distinct forms, Darwin eventually concluded, arose from an evolutionary process of specialization.

Finch beaks, Darwin realized, reflect the principle that Louis Sullivan would later describe by the phrase “form follows function.” Birds that eat large seeds have thick beaks that act like heavy pliers, while those that eat small seeds have sharp beaks like needle-nosed pliers. These distinct forms, Darwin eventually concluded, arose from an evolutionary process of specialization. This modern diagram shows the resultant pattern of so-called adaptive radiation. Clearly, this specialization process is highly non-linear. In art history, one can find similar patterns of specialization and differentiation.

This modern diagram shows the resultant pattern of so-called adaptive radiation. Clearly, this specialization process is highly non-linear. In art history, one can find similar patterns of specialization and differentiation. In the history of Gothic architecture, for example, scholars can clearly recognize the radiation of ideas from the Bourges Cathedral workshop into Tours, Toledo, Coutances, Le Mans and other centers. The great churches in these cities have therefore sometimes been treated as belonging to a “school of Bourges,” despite the many important differences between them.

In the history of Gothic architecture, for example, scholars can clearly recognize the radiation of ideas from the Bourges Cathedral workshop into Tours, Toledo, Coutances, Le Mans and other centers. The great churches in these cities have therefore sometimes been treated as belonging to a “school of Bourges,” despite the many important differences between them. Understanding of evolutionary patterns can help to make sense of formal relationships that might otherwise be overlooked, in both art history and in natural history. That lesson can be seen not only in cathedrals, and in Riegl’s study of arabesques, but in the specialization of vertebrate limbs into fins, wings, flippers, and hands. The key concept, in these cases, is that of homology, the idea that seemingly dissimilar forms are actually modified versions of the same original structures.

Understanding of evolutionary patterns can help to make sense of formal relationships that might otherwise be overlooked, in both art history and in natural history. That lesson can be seen not only in cathedrals, and in Riegl’s study of arabesques, but in the specialization of vertebrate limbs into fins, wings, flippers, and hands. The key concept, in these cases, is that of homology, the idea that seemingly dissimilar forms are actually modified versions of the same original structures. In other cases, conversely, superficial resemblances can arise from originally distinct lineages through the process of convergent evolution. Sharks, dolphins, and the extinct reptiles known as ichthyosaurs all share the same streamlined shape, which is well optimized for swimming, even though they are not close cousins. In the history of world architecture, meanwhile, superficially similar pyramidal temple structures have been erected by many civilizations, from Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica, not because of any direct cross-cultural contact, but because this design allows builders with fairly primitive technology to create durable masonry structures with visual power of height.

In other cases, conversely, superficial resemblances can arise from originally distinct lineages through the process of convergent evolution. Sharks, dolphins, and the extinct reptiles known as ichthyosaurs all share the same streamlined shape, which is well optimized for swimming, even though they are not close cousins. In the history of world architecture, meanwhile, superficially similar pyramidal temple structures have been erected by many civilizations, from Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica, not because of any direct cross-cultural contact, but because this design allows builders with fairly primitive technology to create durable masonry structures with visual power of height. Within individual populations or cultural spheres, competitive arms-races can lead to the development of spectacular and even impractical new forms. The beautiful but cumbersome tail of the male peacock resulted from such an arms-race in the natural world.

Within individual populations or cultural spheres, competitive arms-races can lead to the development of spectacular and even impractical new forms. The beautiful but cumbersome tail of the male peacock resulted from such an arms-race in the natural world. In art, such seemingly superfluous elaboration can be seen in Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts…

In art, such seemingly superfluous elaboration can be seen in Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts… …particularly in the so-called carpet pages that include no text at all. Competition among artists, rather than functional need, surely helped to motivate the creation of such stunning displays.

…particularly in the so-called carpet pages that include no text at all. Competition among artists, rather than functional need, surely helped to motivate the creation of such stunning displays. The dramatic increases in interior height achieved by Gothic builders in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries reflect such competition in the history of architecture. Seen from the outside, such developmental trajectories can appear pre-determined, but there is nothing truly teleological about these competitive dynamics. Instead, they reflect what Gombrich called the logic of the situation, in which certain features are amplified so long as selection pressures and reception reinforce them.

The dramatic increases in interior height achieved by Gothic builders in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries reflect such competition in the history of architecture. Seen from the outside, such developmental trajectories can appear pre-determined, but there is nothing truly teleological about these competitive dynamics. Instead, they reflect what Gombrich called the logic of the situation, in which certain features are amplified so long as selection pressures and reception reinforce them. It is important to emphasize, also, that individual developmental sequences such as these exist within the larger frameworks of natural and cultural history, which display no such simple patterns in their global structure.

It is important to emphasize, also, that individual developmental sequences such as these exist within the larger frameworks of natural and cultural history, which display no such simple patterns in their global structure. In the natural world, types that arose long ago, such as conifers coexist side by side with more recently evolved species, including flowering plants and humans. In the art-historical world, similarly, certain ancient types such as the Egyptian temple could continue to be built in a largely traditional manner for well over a millennium, while architectural styles changed comparatively rapidly in the nearby Greek world. Even within a given culture, rates of artistic change can differ radically.

In the natural world, types that arose long ago, such as conifers coexist side by side with more recently evolved species, including flowering plants and humans. In the art-historical world, similarly, certain ancient types such as the Egyptian temple could continue to be built in a largely traditional manner for well over a millennium, while architectural styles changed comparatively rapidly in the nearby Greek world. Even within a given culture, rates of artistic change can differ radically. The embrace of realism in the representational arts of northern Europe around 1400, for example, was not accompanied by similarly revolutionary changes in architecture, since Gothic design remained fashionable for another century, as this famous painting by Jan van Eyck reminds us.

The embrace of realism in the representational arts of northern Europe around 1400, for example, was not accompanied by similarly revolutionary changes in architecture, since Gothic design remained fashionable for another century, as this famous painting by Jan van Eyck reminds us. The history of Gothic architecture, I would argue, has much in common with the history of dinosaurs. Gothic cathedrals and dinosaurs were large, spectacular, and successful, dominating their environments for long periods of time. Neither succumbed to senescence, since species and art movements, unlike individual organisms, have no fixed life spans. Instead, both eventually succumbed to rapid changes of climate.

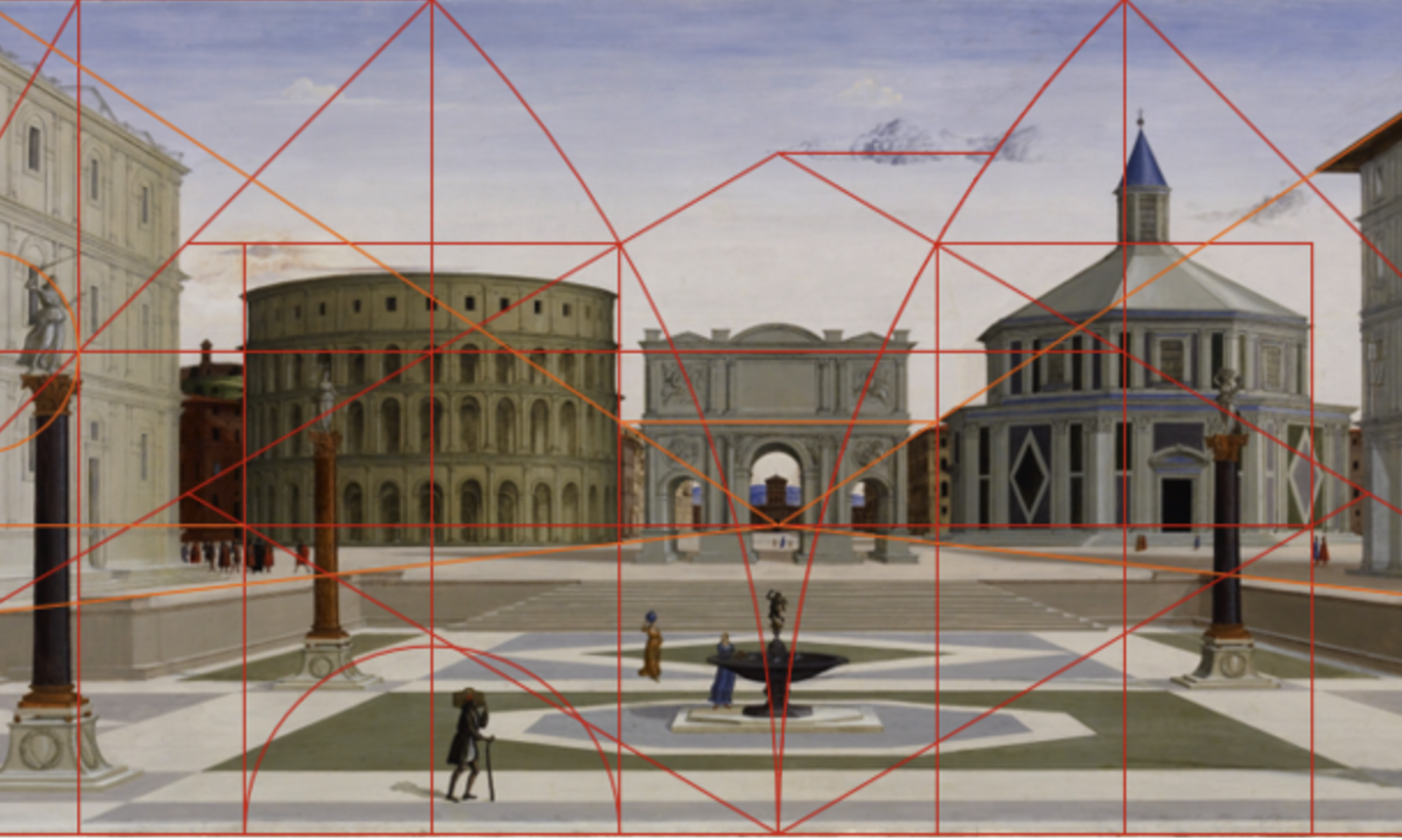

The history of Gothic architecture, I would argue, has much in common with the history of dinosaurs. Gothic cathedrals and dinosaurs were large, spectacular, and successful, dominating their environments for long periods of time. Neither succumbed to senescence, since species and art movements, unlike individual organisms, have no fixed life spans. Instead, both eventually succumbed to rapid changes of climate. Roughly 65 million years ago, a comet or meteor collision set off a change in the terrestrial climate that doomed many species, not just the dinosaurs. And, in the decades around 1500, the spread of humanism, the growth of centralized monarchies, and the Reformation all contributed to a change in the cultural climate that quickly rendered medieval art and architecture obsolete. As these parallels suggest, a broadly Darwinian framework can effectively embrace the complexity and contingency of both cultural and natural history.

Roughly 65 million years ago, a comet or meteor collision set off a change in the terrestrial climate that doomed many species, not just the dinosaurs. And, in the decades around 1500, the spread of humanism, the growth of centralized monarchies, and the Reformation all contributed to a change in the cultural climate that quickly rendered medieval art and architecture obsolete. As these parallels suggest, a broadly Darwinian framework can effectively embrace the complexity and contingency of both cultural and natural history. Indeed, I would argue that the Darwinian paradigm makes far better sense for the study of art history than the older and simpler Vasarian and Hegelian models of history, and their still-fashionable derivatives. The Vasarian comparison of art movements to individual life-spans acts as a procrustean bed of sorts, implicitly devaluing early and late stylistic phases. The less judgmental but equally linear and deterministic Hegelian scheme models the facts of history almost equally poorly. For these reasons, among others I’ll discuss shortly, I believe that art historians have much to gain by considering Darwinian evolutionary theory.

Indeed, I would argue that the Darwinian paradigm makes far better sense for the study of art history than the older and simpler Vasarian and Hegelian models of history, and their still-fashionable derivatives. The Vasarian comparison of art movements to individual life-spans acts as a procrustean bed of sorts, implicitly devaluing early and late stylistic phases. The less judgmental but equally linear and deterministic Hegelian scheme models the facts of history almost equally poorly. For these reasons, among others I’ll discuss shortly, I believe that art historians have much to gain by considering Darwinian evolutionary theory. At this point, some of you are probably thinking “this is an old argument. Art historians have been paying attention to Darwinism ever since the publication of On the Origin of Species back in 1859.” And, indeed, there’s some truth to that claim. When I first began to consider this issue several years ago, I began to find instances where Darwinian language, at least, began to work its way into art-historical writing.

At this point, some of you are probably thinking “this is an old argument. Art historians have been paying attention to Darwinism ever since the publication of On the Origin of Species back in 1859.” And, indeed, there’s some truth to that claim. When I first began to consider this issue several years ago, I began to find instances where Darwinian language, at least, began to work its way into art-historical writing. Some authors, like Gottfried Semper and Heinrich Wölfflin, shown here, engaged with Darwin’s writings quite directly and self-consciously. Others, like Henri Bergson, embraced a more impressionistic and even mystical view of evolution. Broadly speaking, however, the art-historical community has engaged surprisingly little with Darwinian evolutionary theory.

Some authors, like Gottfried Semper and Heinrich Wölfflin, shown here, engaged with Darwin’s writings quite directly and self-consciously. Others, like Henri Bergson, embraced a more impressionistic and even mystical view of evolution. Broadly speaking, however, the art-historical community has engaged surprisingly little with Darwinian evolutionary theory. Riegl criticized Semper’s followers for their naïve Darwinism, even though his own later writings, such as the fragments of the Historische Grammatik that were still unpublished upon his death in 1905, postulate a view of artistic development through cultural selection that recalls Darwinian evolution more closely than his earlier and more Hegelian Stilfragen. Henri Focillon faulted evolutionism for what he called its its “deceptive orderliness” and “single-minded directness,” even though Darwinian evolution is neither orderly nor goal-directed. Focillon, in this instance, appears to have wrongly associated evolution with the Hegelian idea of progressive development that he so emphatically opposed.

Riegl criticized Semper’s followers for their naïve Darwinism, even though his own later writings, such as the fragments of the Historische Grammatik that were still unpublished upon his death in 1905, postulate a view of artistic development through cultural selection that recalls Darwinian evolution more closely than his earlier and more Hegelian Stilfragen. Henri Focillon faulted evolutionism for what he called its its “deceptive orderliness” and “single-minded directness,” even though Darwinian evolution is neither orderly nor goal-directed. Focillon, in this instance, appears to have wrongly associated evolution with the Hegelian idea of progressive development that he so emphatically opposed. Gombrich, as we have seen, dismissed evolutionism for similar reasons, even though his own work translates easily into the Darwinian intellectual framework that I have been discussing. And, in the past half century, genuinely Darwinian theory has provided little substantive grist for the mills of art-historical writing.

Gombrich, as we have seen, dismissed evolutionism for similar reasons, even though his own work translates easily into the Darwinian intellectual framework that I have been discussing. And, in the past half century, genuinely Darwinian theory has provided little substantive grist for the mills of art-historical writing. In a 2001 article on the problem of evolutionism, therefore, Eric Fernie rightly distinguished between the ways biologists and art historians have used evolutionary language, observing that humanists still tend to associate the term “evolution” with progressive linear development. After making this important point, though, Fernie advances what I see as a rather perverse argument for the dismissal of evolutionary language from art historical discourse, suggesting that the usefulness of evolutionary language in art history should be judged by how it has been applied rather than how it could be. To me, at least, this sounds rather like an argument that knives should be dismissed as useless because they don’t cut well when held upside-down. Surely it makes sense to experiment with using a tool properly before setting it aside. I would argue, therefore, that art historians should carefully consider the possible relevance of evolutionary theory, instead of rejecting out of hand this powerful framework for the discussion of formal change over time. I recognize, of course, that the mechanisms for change are very different in art history than in biology.

In a 2001 article on the problem of evolutionism, therefore, Eric Fernie rightly distinguished between the ways biologists and art historians have used evolutionary language, observing that humanists still tend to associate the term “evolution” with progressive linear development. After making this important point, though, Fernie advances what I see as a rather perverse argument for the dismissal of evolutionary language from art historical discourse, suggesting that the usefulness of evolutionary language in art history should be judged by how it has been applied rather than how it could be. To me, at least, this sounds rather like an argument that knives should be dismissed as useless because they don’t cut well when held upside-down. Surely it makes sense to experiment with using a tool properly before setting it aside. I would argue, therefore, that art historians should carefully consider the possible relevance of evolutionary theory, instead of rejecting out of hand this powerful framework for the discussion of formal change over time. I recognize, of course, that the mechanisms for change are very different in art history than in biology. Artistic conception involves creativity and self-conscious human agency, rather than the comparatively far simpler process of genetic recombination, illustrated with a basic example in the diagram here. The power of Darwin’s theoretical model, though, does not depend on the precise mechanism of inheritance. Darwin himself, in fact, knew nothing of modern genetics, a field that began to flower, if you’ll excuse the pun, only with the rediscovery around 1900 of Gregor Mendel’s pioneering work from the 1860s. Darwin certainly understood, though, that the vast majority of advanced plants and animals have exactly two parents each, and that they inherit directly from that preceding generation.

Artistic conception involves creativity and self-conscious human agency, rather than the comparatively far simpler process of genetic recombination, illustrated with a basic example in the diagram here. The power of Darwin’s theoretical model, though, does not depend on the precise mechanism of inheritance. Darwin himself, in fact, knew nothing of modern genetics, a field that began to flower, if you’ll excuse the pun, only with the rediscovery around 1900 of Gregor Mendel’s pioneering work from the 1860s. Darwin certainly understood, though, that the vast majority of advanced plants and animals have exactly two parents each, and that they inherit directly from that preceding generation. This means, on a larger scale, that all the species in the world can be diagrammed on a branching tree of life. At right you see a page from one of Darwin’s notebooks, showing that he appreciated this basic idea already in 1837. At left, meanwhile, you see a modern tree of life diagram, in which the origin of life is shown at the top. Such diagrams, called cladograms, show how progressive differentiation events have produced the full diversity of life. Some of these branches of the tree, of course, have been pruned over time by extinction.

This means, on a larger scale, that all the species in the world can be diagrammed on a branching tree of life. At right you see a page from one of Darwin’s notebooks, showing that he appreciated this basic idea already in 1837. At left, meanwhile, you see a modern tree of life diagram, in which the origin of life is shown at the top. Such diagrams, called cladograms, show how progressive differentiation events have produced the full diversity of life. Some of these branches of the tree, of course, have been pruned over time by extinction. Here a related graphic, known as a Mae West diagram, indicates the waxing and waning of species numbers in its swelling curves, with the vertical axis representing the passage of time, starting from the bottom. Here, for example, we see the waning and eventual extinction of the Placoderms, a group of armored fish. Graphic representations of art history, in general, will not have the simple tree-like branching structure seen in these three diagrams.

Here a related graphic, known as a Mae West diagram, indicates the waxing and waning of species numbers in its swelling curves, with the vertical axis representing the passage of time, starting from the bottom. Here, for example, we see the waning and eventual extinction of the Placoderms, a group of armored fish. Graphic representations of art history, in general, will not have the simple tree-like branching structure seen in these three diagrams. Alfred Barr’s famous diagram showing the relationship between movements in modern art, for example, includes loops and intersections as well as branches, giving the overall structure a very different topology than the evolutionary diagrams. This complexity results from the fact that artists can be inspired by many different precedents, and not just by one set of parents. These influences may be ancient or largely foreign to the artist’s cultural tradition.

Alfred Barr’s famous diagram showing the relationship between movements in modern art, for example, includes loops and intersections as well as branches, giving the overall structure a very different topology than the evolutionary diagrams. This complexity results from the fact that artists can be inspired by many different precedents, and not just by one set of parents. These influences may be ancient or largely foreign to the artist’s cultural tradition. Picasso could incorporate African mask forms in Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon, for example. His creative process, therefore, calls to mind modern gene-splicing techniques rather than the straightforward speciation seen in nature. Biologists have been able to abandon vague categories like “fish-shaped animals” because they recognize that whales and ichthyosaurs came to have fishlike shapes without being directly influenced by fish. Comparably vague terms based on external characteristics, however, are likely to remain important in art-historical discourse.

Picasso could incorporate African mask forms in Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon, for example. His creative process, therefore, calls to mind modern gene-splicing techniques rather than the straightforward speciation seen in nature. Biologists have been able to abandon vague categories like “fish-shaped animals” because they recognize that whales and ichthyosaurs came to have fishlike shapes without being directly influenced by fish. Comparably vague terms based on external characteristics, however, are likely to remain important in art-historical discourse. The term "classicizing sculpture," for example, proves useful in the case of Nicola Pisano because his work cannot readily be explained without consideration of late antique prototypes as well as his own thirteenth-century Italian milieu. Art historical taxonomy, therefore, can never be reduced to a single definitive evolutionarily-based system in the same sense that biological taxonomy, at least in principle, can be. As these examples should begin to demonstrate, I recognize that the techniques and structures of evolutionary biology cannot be imported into art history wholesale and unmodified.

The term "classicizing sculpture," for example, proves useful in the case of Nicola Pisano because his work cannot readily be explained without consideration of late antique prototypes as well as his own thirteenth-century Italian milieu. Art historical taxonomy, therefore, can never be reduced to a single definitive evolutionarily-based system in the same sense that biological taxonomy, at least in principle, can be. As these examples should begin to demonstrate, I recognize that the techniques and structures of evolutionary biology cannot be imported into art history wholesale and unmodified. But, as I noted in my introduction, I do believe passionately that engagement with this intellectual legacy can benefit the art-historical community, for both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons. On the intrinsic front, I really do think that Darwinian theory provides a better framework for the understanding of formal change over time than the Vasarian and Hegelian models that have dominated art-historical discourse. Darwinian evolution is non-linear, non-teleological, and it effectively embraces the complexity and contingency of history. Crucially, too, the Darwinian paradigm reveals that formal differences are best understood as the results of history, rather than as fixed and absolute givens. Darwinism thus serves to combat essentialism. It is this challenge to rigid essentialism, in fact, that the noted evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr recently identified as Darwin’s most fundamental contribution to the world of ideas.

But, as I noted in my introduction, I do believe passionately that engagement with this intellectual legacy can benefit the art-historical community, for both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons. On the intrinsic front, I really do think that Darwinian theory provides a better framework for the understanding of formal change over time than the Vasarian and Hegelian models that have dominated art-historical discourse. Darwinian evolution is non-linear, non-teleological, and it effectively embraces the complexity and contingency of history. Crucially, too, the Darwinian paradigm reveals that formal differences are best understood as the results of history, rather than as fixed and absolute givens. Darwinism thus serves to combat essentialism. It is this challenge to rigid essentialism, in fact, that the noted evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr recently identified as Darwin’s most fundamental contribution to the world of ideas. In all these respects, the Darwinian paradigm thus meshes smoothly with the sophisticated interpretive schemes developed by art historians such as Gombrich, who was particularly concerned to challenge what he saw as the quasi-totalitarian essentialism of the Hegelian worldview. As we have seen, though, Gombrich identified the word “evolutionism” with Hegel more than with Darwin, and he seems never to have fully appreciated the relevance of Darwinian theory for his own scholarly project. One reason for this, ironically, may have been his close association with the noted philosopher of science Karl Popper, who trained as a physicist.

In all these respects, the Darwinian paradigm thus meshes smoothly with the sophisticated interpretive schemes developed by art historians such as Gombrich, who was particularly concerned to challenge what he saw as the quasi-totalitarian essentialism of the Hegelian worldview. As we have seen, though, Gombrich identified the word “evolutionism” with Hegel more than with Darwin, and he seems never to have fully appreciated the relevance of Darwinian theory for his own scholarly project. One reason for this, ironically, may have been his close association with the noted philosopher of science Karl Popper, who trained as a physicist. Popper’s extensive and influential work on the epistemology of science emphasizes “falsifiability,” the notion that a scientific theory must make testable predictions. Theories whose predictions fail to match the results of experiment would then be thrown out or modified, leading to a kind of intellectual evolution towards ever more precise theories. Because physics is a discipline devoted to the study of timeless universal principles, Popper could afford to place a premium on prediction and experimentation. Disciplines like evolutionary biology, geology, and cosmology, however, deal necessarily with the past, and they therefore cannot be based on prediction in the same strict sense as physics. In both epistemological and methodological terms, therefore, these scientific disciplines have much in common with humanistic disciplines like art history. Ernst Mayr makes this very point when discussing Darwin’s intellectual legacy, suggesting optimistically that such parallels between certain scientific and humanistic disciplines should help open up the lines of communication between the “two cultures” that had been identified by C.P. Snow. Philosopher of science Daniel Dennett made much the same argument a decade earlier, in his brilliantly provocative book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea.

Popper’s extensive and influential work on the epistemology of science emphasizes “falsifiability,” the notion that a scientific theory must make testable predictions. Theories whose predictions fail to match the results of experiment would then be thrown out or modified, leading to a kind of intellectual evolution towards ever more precise theories. Because physics is a discipline devoted to the study of timeless universal principles, Popper could afford to place a premium on prediction and experimentation. Disciplines like evolutionary biology, geology, and cosmology, however, deal necessarily with the past, and they therefore cannot be based on prediction in the same strict sense as physics. In both epistemological and methodological terms, therefore, these scientific disciplines have much in common with humanistic disciplines like art history. Ernst Mayr makes this very point when discussing Darwin’s intellectual legacy, suggesting optimistically that such parallels between certain scientific and humanistic disciplines should help open up the lines of communication between the “two cultures” that had been identified by C.P. Snow. Philosopher of science Daniel Dennett made much the same argument a decade earlier, in his brilliantly provocative book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. This brings me to my closing point, about the extrinsic advantages, for art historians, of engaging with Darwinian theory. There is far more at stake here than just finding a convenient intellectual framework that can embrace the complexity of art history, as important as I think that is. Nor is it simply a question of gaining a new evolutionary perspective on the structure of the art-making human mind, although this, too, is a crucial point that Lauren Golden’s paper will address in a few minutes. In the present intellectual, political, and institutional climate, art historians and other humanists risk losing resources and relevance if we cut ourselves off from the discourse of the sciences. Most of us, after all, are employed in colleges or divisions of arts and sciences, and scientists should, for many reasons, be our natural allies within the academy. All of us, after all, are engaged in same basic project, using evidence and argument to push back the frontiers of knowledge.

This brings me to my closing point, about the extrinsic advantages, for art historians, of engaging with Darwinian theory. There is far more at stake here than just finding a convenient intellectual framework that can embrace the complexity of art history, as important as I think that is. Nor is it simply a question of gaining a new evolutionary perspective on the structure of the art-making human mind, although this, too, is a crucial point that Lauren Golden’s paper will address in a few minutes. In the present intellectual, political, and institutional climate, art historians and other humanists risk losing resources and relevance if we cut ourselves off from the discourse of the sciences. Most of us, after all, are employed in colleges or divisions of arts and sciences, and scientists should, for many reasons, be our natural allies within the academy. All of us, after all, are engaged in same basic project, using evidence and argument to push back the frontiers of knowledge. But, especially in the half-century since C.P. Snow popularized the idea of the “two cultures,” relations between the sciences and the humanities have been marked by increasing mutual suspicion and misunderstanding, culminating in incidents such as physicist Alan Sokal’s devastating hoax submission to the journal Social Text in 1996. Art historians and humanists have good reason to worry about this divide, not least because the sciences and medicine command a large and increasing share of university budgets. This divide, moreover, tends to discredit the academy as a whole, an important consideration given the rampant anti-intellectualism of modern American society. In an era where schoolboards cut funding for the arts even as they debate the teaching of scripturally-based creationism and so-called Intelligent Design in place of Darwinian evolution, the internal coherence of the academy becomes especially important for setting the tone of public life.

But, especially in the half-century since C.P. Snow popularized the idea of the “two cultures,” relations between the sciences and the humanities have been marked by increasing mutual suspicion and misunderstanding, culminating in incidents such as physicist Alan Sokal’s devastating hoax submission to the journal Social Text in 1996. Art historians and humanists have good reason to worry about this divide, not least because the sciences and medicine command a large and increasing share of university budgets. This divide, moreover, tends to discredit the academy as a whole, an important consideration given the rampant anti-intellectualism of modern American society. In an era where schoolboards cut funding for the arts even as they debate the teaching of scripturally-based creationism and so-called Intelligent Design in place of Darwinian evolution, the internal coherence of the academy becomes especially important for setting the tone of public life. Scientists and humanists both have much to be proud of, and active dialog between the two groups would likely foster increased mutual respect as well as mutual understanding. Humanists may be positively surprised by the power, lucidity, and relevance of scientific intellectual models. Scientists, conversely, may be struck by the subtlety and complexity of the problems that humanists confront in their work, which make the substantial achievements of humanistic scholarship all the more impressive.

Scientists and humanists both have much to be proud of, and active dialog between the two groups would likely foster increased mutual respect as well as mutual understanding. Humanists may be positively surprised by the power, lucidity, and relevance of scientific intellectual models. Scientists, conversely, may be struck by the subtlety and complexity of the problems that humanists confront in their work, which make the substantial achievements of humanistic scholarship all the more impressive. The fact that the topology of artistic influence is far more intricate than that of evolutionary biology, for example, helps to demonstrate why cultural history cannot be treated in precisely the same way as natural history. Thus, while some might worry that exploration of the analogies between the arts and the sciences would lead to the colonization of one discourse by the other, it seems far more probable that such dialog would underline the autonomy and the dignity of each. Since the academy in the early twenty-first century often seems both divided against itself and marginalized in the society at large, the potential benefits of cross-disciplinary communication are simply too great to ignore.

The fact that the topology of artistic influence is far more intricate than that of evolutionary biology, for example, helps to demonstrate why cultural history cannot be treated in precisely the same way as natural history. Thus, while some might worry that exploration of the analogies between the arts and the sciences would lead to the colonization of one discourse by the other, it seems far more probable that such dialog would underline the autonomy and the dignity of each. Since the academy in the early twenty-first century often seems both divided against itself and marginalized in the society at large, the potential benefits of cross-disciplinary communication are simply too great to ignore. Based on a CAA presentation given in 2008 by Robert Bork.

Based on a CAA presentation given in 2008 by Robert Bork.