This painting depicts six nymphs tending to Vulcan, who had been hurled from Olympus.

This painting depicts six nymphs tending to Vulcan, who had been hurled from Olympus. The panel nearly but not perfectly square, being slightly wider than it is tall, as one can see from the fact that narrow strips border the sides of the circle inscribed within its top and bottom margins. The circle suggestively traces out a number of elements in the painting. Starting at the left center and moving clockwise, these include the side of the left nymph’s basket, details of the foliage in the trees , and most obviously the arm of the nymph at lower right. A square inscribed within this circle contains the faces of all of the nymphs, even though the heads of three of them protrude from this frame. Vulcan seems to kneel on the bottom of the square, whose top edge corresponds to a prominent break in the cloud bank above. The diagonals of the square appear to govern the pose of the central nymph and her companion to the upper right. The diagonal rising from left to right also aligns closely with a band of shadow in the grass at lower left.

The panel nearly but not perfectly square, being slightly wider than it is tall, as one can see from the fact that narrow strips border the sides of the circle inscribed within its top and bottom margins. The circle suggestively traces out a number of elements in the painting. Starting at the left center and moving clockwise, these include the side of the left nymph’s basket, details of the foliage in the trees , and most obviously the arm of the nymph at lower right. A square inscribed within this circle contains the faces of all of the nymphs, even though the heads of three of them protrude from this frame. Vulcan seems to kneel on the bottom of the square, whose top edge corresponds to a prominent break in the cloud bank above. The diagonals of the square appear to govern the pose of the central nymph and her companion to the upper right. The diagonal rising from left to right also aligns closely with a band of shadow in the grass at lower left. When an octagon is circumscribed around the central circle, it can be seen that the radii to its corners serve to locate many elements in the composition. Starting at the top left center and moving clockwise, these include the eye of the nymph at left, the shape of the trees at upper left, the placement of the tree and landforms at upper right, the shoulder of the rightmost standing nymph, her foot position, the line of her kneeling companion’s gaze, the placement of Vulcan’s right foot, the angle of his right arm and face, and the points on the two nymphs at left where their bare legs emerge from their garb.

When an octagon is circumscribed around the central circle, it can be seen that the radii to its corners serve to locate many elements in the composition. Starting at the top left center and moving clockwise, these include the eye of the nymph at left, the shape of the trees at upper left, the placement of the tree and landforms at upper right, the shoulder of the rightmost standing nymph, her foot position, the line of her kneeling companion’s gaze, the placement of Vulcan’s right foot, the angle of his right arm and face, and the points on the two nymphs at left where their bare legs emerge from their garb. The overall shape of the panel is set by adding to the sides of the octagon narrow strips whose width equals one third of the interval between the octagon and its inscribing square, as the small yellow circles indicate.

The overall shape of the panel is set by adding to the sides of the octagon narrow strips whose width equals one third of the interval between the octagon and its inscribing square, as the small yellow circles indicate. When green diagonals are extended from the endpoints of these circles’ radii, one finds an armature that helps to establish other elements of the composition. The uppermost left diagonal, for example, traces the treebranch at left, the hand of leftmost nymph, and the pattern of the adjacent tree’s foliage. The upper right diagonal, similarly, traces not only the wing of the upper bird, but also the gaze of the two standing nymphs at right.

When green diagonals are extended from the endpoints of these circles’ radii, one finds an armature that helps to establish other elements of the composition. The uppermost left diagonal, for example, traces the treebranch at left, the hand of leftmost nymph, and the pattern of the adjacent tree’s foliage. The upper right diagonal, similarly, traces not only the wing of the upper bird, but also the gaze of the two standing nymphs at right. Finally, this system can be extended by using the full width of the panel, rather than just the largest square contained by it. So, example, the rightmost nymph steps on the ray of an octagon extended to this margin of the panel. Also, when 45-degree diagonals are launched from the corners of the panel, and reflected around the red diagonals of the large square, a blue-bordered X results, whose central diamond coincides with the chest of the central nymph. Her head fits into the upper left branch of the X, while here upper arm and left leg fig into the lower right branch. The lower left branch of the X aligns with her shoulders, Vulcan’s eye, and the face of the second standing nymph from the right. Further details can be found within this framework, but those cited already should suffice to demonstrate the relevance of this overall armature for the composition.

Finally, this system can be extended by using the full width of the panel, rather than just the largest square contained by it. So, example, the rightmost nymph steps on the ray of an octagon extended to this margin of the panel. Also, when 45-degree diagonals are launched from the corners of the panel, and reflected around the red diagonals of the large square, a blue-bordered X results, whose central diamond coincides with the chest of the central nymph. Her head fits into the upper left branch of the X, while here upper arm and left leg fig into the lower right branch. The lower left branch of the X aligns with her shoulders, Vulcan’s eye, and the face of the second standing nymph from the right. Further details can be found within this framework, but those cited already should suffice to demonstrate the relevance of this overall armature for the composition. This painting is the property of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, in Hartford, Connecticut. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piero_di_cosimo,_ritrovamento_di_vulcano_2.jpg

This painting is the property of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, in Hartford, Connecticut. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piero_di_cosimo,_ritrovamento_di_vulcano_2.jpg

Piero della Francesca- Brera Alterpiece

Here is the so-called Brera Altarpiece, painted by Piero della Francesca, showing the condottiere Federico da Montefeltro in adoration of the Virgin and Child, surrounded by saints. Piero della Francesca is famous for his writings on perspective and solid geometry, but this composition was actually governed by a simple two-dimensional geometrical scheme whose logic would have been familiar to any compass-wielding Gothic architect or early medieval craftsman. To see this, start by considering a few details of the painting. First, its sides have been slightly trimmed, and the elbows of John the Baptist at left, and of Andrew at right, thus appear slightly truncated. Second, these two saints hold their attributes in ways that serve as geometrical markers, which is particularly conspicuous in the case of the Baptist’s staff. Both the staff and Andrew’s book are aligned at 22.5 degrees from the vertical.

Here is the so-called Brera Altarpiece, painted by Piero della Francesca, showing the condottiere Federico da Montefeltro in adoration of the Virgin and Child, surrounded by saints. Piero della Francesca is famous for his writings on perspective and solid geometry, but this composition was actually governed by a simple two-dimensional geometrical scheme whose logic would have been familiar to any compass-wielding Gothic architect or early medieval craftsman. To see this, start by considering a few details of the painting. First, its sides have been slightly trimmed, and the elbows of John the Baptist at left, and of Andrew at right, thus appear slightly truncated. Second, these two saints hold their attributes in ways that serve as geometrical markers, which is particularly conspicuous in the case of the Baptist’s staff. Both the staff and Andrew’s book are aligned at 22.5 degrees from the vertical. Together they thus describe the converging sides of a triangle with an interior angle of 45 degrees, which can be understood as one eighth of a regular octagon. The baseline of this triangle likely corresponds to the original width of the panel, as the red verticals here indicate. A related construction correctly gives the height of the panel.

Together they thus describe the converging sides of a triangle with an interior angle of 45 degrees, which can be understood as one eighth of a regular octagon. The baseline of this triangle likely corresponds to the original width of the panel, as the red verticals here indicate. A related construction correctly gives the height of the panel. Here, at the top of the image, five facets of an orange octagon are centered on the apex of the red wedge and framed by the red verticals. The upper corners of the octagon’s lateral facets locate the top edge of the panel. In the bottom half of the image, an orange circle fits within the square left over beneath the octagon’s lateral facets, and a square can be inscribed within that circle. Notice that the vertical facets of the square locate the corners of the pilasters on the wall behind the saints, and that its top facet locates the bottom edge of the pilaster capitals.

Here, at the top of the image, five facets of an orange octagon are centered on the apex of the red wedge and framed by the red verticals. The upper corners of the octagon’s lateral facets locate the top edge of the panel. In the bottom half of the image, an orange circle fits within the square left over beneath the octagon’s lateral facets, and a square can be inscribed within that circle. Notice that the vertical facets of the square locate the corners of the pilasters on the wall behind the saints, and that its top facet locates the bottom edge of the pilaster capitals. Next, another quadrature step inwards can be performed by inscribing a yellow circle within the square, and a yellow square within the new circle. Note that the Virgin’s blue cloak just fills the arc of the yellow circle, that the right lower corner of the yellow square locates Federico’s elbow, and that the left yellow vertical defines the midline of Saint Jerome’s bifurcated garment.

Next, another quadrature step inwards can be performed by inscribing a yellow circle within the square, and a yellow square within the new circle. Note that the Virgin’s blue cloak just fills the arc of the yellow circle, that the right lower corner of the yellow square locates Federico’s elbow, and that the left yellow vertical defines the midline of Saint Jerome’s bifurcated garment. One large green triangle, sharing its baseline with the yellow square, has its upper vertex in the Virgin’s left eye socket, since she inclines her head slightly to one side as she gazes at her child. The child’s body lies along of 30-degree slope departing from Federico’s elbow, which also locates the elbow of the angel to the left of the Virgin. The comparable point on the right locates the hand of Saint Francis. In the upper section of the panel, meanwhile, octature creates a new green horizontal just above the orange one, by inscribing arcs within the lateral wedges of the orange octagon. This new green horizontal matters because it serves as the geometrical baseline for the painting’s upper architectural structure. It coincides with the top edge of the entablature on either side of the main niche.

One large green triangle, sharing its baseline with the yellow square, has its upper vertex in the Virgin’s left eye socket, since she inclines her head slightly to one side as she gazes at her child. The child’s body lies along of 30-degree slope departing from Federico’s elbow, which also locates the elbow of the angel to the left of the Virgin. The comparable point on the right locates the hand of Saint Francis. In the upper section of the panel, meanwhile, octature creates a new green horizontal just above the orange one, by inscribing arcs within the lateral wedges of the orange octagon. This new green horizontal matters because it serves as the geometrical baseline for the painting’s upper architectural structure. It coincides with the top edge of the entablature on either side of the main niche. By constructing nested blue octagons and semicircles centered on this level and framed by the orange uprights, moreover, both the location and the thickness of the arch over the main niche can be determined. The large blue arc circumscribing the orange octagon and sweeping through the Virgin’s face also locates the eye level of most of the saints. That relationship is only approximate, but the bottom point on this arc also serves quite precisely as the point of convergence for the perspectival system defined by the converging lines of the entablatures, as the blue raking lines along the entablatures indicate.

By constructing nested blue octagons and semicircles centered on this level and framed by the orange uprights, moreover, both the location and the thickness of the arch over the main niche can be determined. The large blue arc circumscribing the orange octagon and sweeping through the Virgin’s face also locates the eye level of most of the saints. That relationship is only approximate, but the bottom point on this arc also serves quite precisely as the point of convergence for the perspectival system defined by the converging lines of the entablatures, as the blue raking lines along the entablatures indicate. This painting is the property of the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, Italy. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piero_della_Francesca_046.jpg

This painting is the property of the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, Italy. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piero_della_Francesca_046.jpg

Piero di Cosimo- Catherine

Here is Piero di Cosimo’s depiction of the Virgin and Child adored by saints including Elizabeth of Hungary, at left, and Catherine, at right.

Here is Piero di Cosimo’s depiction of the Virgin and Child adored by saints including Elizabeth of Hungary, at left, and Catherine, at right. The panel is a perfect square. Note that a circle inscribed within this square swings tantalizingly along the side of the cloud at upper left and the putto’s wing, at right. This circle can be understood as just the first in a sequence of compass-drawn quadrature steps

The panel is a perfect square. Note that a circle inscribed within this square swings tantalizingly along the side of the cloud at upper left and the putto’s wing, at right. This circle can be understood as just the first in a sequence of compass-drawn quadrature steps The base of the orange square inscribed within the red circle coincides with the edge of the lowest step on the Virgin’s throne, and the left and right midpoints of that square locate the hands of Saints Peter and John, who flank the composition. Here also rays have been added subdividing the composition into 24 equal wedges; note that these align with elements including the outer visible tiles in the floor in front of the throne.

The base of the orange square inscribed within the red circle coincides with the edge of the lowest step on the Virgin’s throne, and the left and right midpoints of that square locate the hands of Saints Peter and John, who flank the composition. Here also rays have been added subdividing the composition into 24 equal wedges; note that these align with elements including the outer visible tiles in the floor in front of the throne. Continuing inwards, further concentric circles divide the saints into ranks of proximity to the Child

Continuing inwards, further concentric circles divide the saints into ranks of proximity to the Child Only Elizabeth and Catherine, for example, have faces within the green square.

Only Elizabeth and Catherine, for example, have faces within the green square. And only Catherine’s hand penetrates into the blue circle that frames the child.

And only Catherine’s hand penetrates into the blue circle that frames the child. The bend of her fingers aligns with the same violet square that frames the child’s leg, and her fingertips penetrate just beyond the circle that frames his shoulder.

The bend of her fingers aligns with the same violet square that frames the child’s leg, and her fingertips penetrate just beyond the circle that frames his shoulder. The horizon line can also be readily found within this framework, as can the curving top edge of the Virgin’s throne.

The horizon line can also be readily found within this framework, as can the curving top edge of the Virgin’s throne. This painting is the property of the John Museo degli Innocenti, Florence, Italy. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Madonna_and_Child_Enthroned_with_Saints_Piero_di_Cosimo.jpg

This painting is the property of the John Museo degli Innocenti, Florence, Italy. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Madonna_and_Child_Enthroned_with_Saints_Piero_di_Cosimo.jpg

Gauguin- “D’où Venons Nous?”

Here is Gauguin’s "D'où Venons Nous?”. A geometrical analysis will show the origins of the composition and the underlying structure.

Here is Gauguin’s "D'où Venons Nous?”. A geometrical analysis will show the origins of the composition and the underlying structure. The red lines create diagonals across the whole painting. Note that the reclining woman at left leans on the rising diagonal, which also defines the lighter colored ground at left of center, the hand of the central nude with the turned back, and the branching of the tree at top right. The falling diagonal defines the changing ground color at left of center and the small child’s leg and loincloth at the lower right.

The red lines create diagonals across the whole painting. Note that the reclining woman at left leans on the rising diagonal, which also defines the lighter colored ground at left of center, the hand of the central nude with the turned back, and the branching of the tree at top right. The falling diagonal defines the changing ground color at left of center and the small child’s leg and loincloth at the lower right.A circle filling the picture’s full height at its center sweeps around the sleeve of the larger child in the foreground, past the rear and elbow of the central nude with the turned back, and through the fruit being grabbed by the main figure near the top.

Starting from the left, two squares are made, each inscribed with the “X” of its diagonals. The figures in the middle ground, walking from the left, stop in front of the vertical margins of these squares.

Next, in orange, the same step with the squares is applied, moving from the right this time. In this case, it is the idol that abuts the margin of the square. The outer pair of red and orange verticals divide the composition into a triptych of sorts, particularly in the upper half of the painting. (Note that the steps in this analysis proceed in the spectral order of the rainbow: first red, then orange, and in subsequent slides yellow, green, blue, and violet.)

Next, in orange, the same step with the squares is applied, moving from the right this time. In this case, it is the idol that abuts the margin of the square. The outer pair of red and orange verticals divide the composition into a triptych of sorts, particularly in the upper half of the painting. (Note that the steps in this analysis proceed in the spectral order of the rainbow: first red, then orange, and in subsequent slides yellow, green, blue, and violet.)

In the left wing of the “triptych,” the steeply falling yellow diagonal passes through the head and body of the reclining woman, whose bracing arm is defined by the yellow vertical halfway across the left “wing.”

In the upper left half of the painting, the yellow horizontal defining the horizon line passes through the intersection of the red and orange diagonals near the idol.

In the middle panel of the “triptych,” the yellow diagonal falling to the orange vertical defines the sloping feet of the idol, the pink feet of the woman in the middle ground, and the ankle joint of the main figure.

In the right panel of the “triptych,” the dog at right leans its paws on the falling diagonal, while the second woman of the seated group rests her elbow on the rising diagonal.

The navel of the idol can be found by drawing a short green horizontal from the intersection of the orange vertical and the falling red diagonal of the painting until it hits the rising red diagonal of the first square. The green vertical descending from the navel subdivides the idol’s legs, but not its head, which is displaced left.

The bright green vertical stands .707 of the way from the left margin of the painting to the right; this is the ratio of a square’s side to its diagonal, which is an interesting relationship to invoke, since the painting is not square.

A green “X” through the bright green vertical defines a green vertical against which the large child in the foreground reclines. The cats climb the rising diagonal of the “X,” while the falling diagonal defines the tilt of the second woman’s head at right, the placement of her hand, and the head/torso junction of the small child. In blue, a circle is drawn at the center of the painting, so that it is tangent to the green vertical against which the older child leans. This circle intersects the diagonals reaching out from the painting center in points that define the blue vertical axis of the main figure, which passes through his navel and along the line separating his thighs.

In blue, a circle is drawn at the center of the painting, so that it is tangent to the green vertical against which the older child leans. This circle intersects the diagonals reaching out from the painting center in points that define the blue vertical axis of the main figure, which passes through his navel and along the line separating his thighs.The blue vertical further to the right, tangent to the original red circle, forms a bookend of sorts for the rear of the first woman in the group at right.

In the left half of the painting, the rising violet diagonal to the top center of the painting intersects the descending red diagonal at a point 2/3 of the way up the painting, defining the height of the brown land at left, and 1/3 of the way across the painting, defining the back of the figure near the idol.

In the middle of the painting, violet lines of 60-degree slope descend from the top of the main figure’s axis. The left line passes along his forearm, arriving at a prominent crease in the sleeve of the large child by the cats. The right line passes along the main figure’s other forearm, along the back of the central seated nude, and along the arm and leg of the first woman in the right-hand group.

A violet line ascending from the base of the blue vertical defines the elbow, wrist, and face, respectively, of the three right-hand women. Voila…

Carpaccio- Saint George and the Dragon

Here is Carpaccio’s painting of Saint George and the Dragon.

Here is Carpaccio’s painting of Saint George and the Dragon. Add red lines from the left corner at 75, 60, 45, 30, and 15 degrees off horizontal. Note that the steepest one, at left, is an axis around which the dragon’s tail oscillates. The vertical dropped from the top of the 60-degree line passes through the right corner of the square-planned tower in the middle ground. Crucially, the vertical dropped from the top of the 30-degree line passes through the point where the lance intersects its crosspiece.

Add red lines from the left corner at 75, 60, 45, 30, and 15 degrees off horizontal. Note that the steepest one, at left, is an axis around which the dragon’s tail oscillates. The vertical dropped from the top of the 60-degree line passes through the right corner of the square-planned tower in the middle ground. Crucially, the vertical dropped from the top of the 30-degree line passes through the point where the lance intersects its crosspiece. Take the lower left corner as the center of a very large octagon whose right-hand facet coincides with the red line dropped from the top of the 45-degree line. A line of slope 22.5 degrees from the lower left corner of the painting intersects the red vertical dropped from the 30-degree red line, thus locating the precise point of the lance/crosspiece intersection.

Take the lower left corner as the center of a very large octagon whose right-hand facet coincides with the red line dropped from the top of the 45-degree line. A line of slope 22.5 degrees from the lower left corner of the painting intersects the red vertical dropped from the 30-degree red line, thus locating the precise point of the lance/crosspiece intersection. Taking that intersection point on the lance as a center, create two dodecagons; one whose lower facet aligns with the bottom of the painting, and a smaller one whose upper facet aligns with the top of the painting. The lance, with its 15-degree slope, passes through corners of these dodecagons. The tree foliage at the upper right also lies along this axis.

Taking that intersection point on the lance as a center, create two dodecagons; one whose lower facet aligns with the bottom of the painting, and a smaller one whose upper facet aligns with the top of the painting. The lance, with its 15-degree slope, passes through corners of these dodecagons. The tree foliage at the upper right also lies along this axis. The right margin of the painting may be found by dropping a 45-degree diagonal down from the uppermost left corner of the small dodecagon down to the bottom margin of the painting; this operation thus sets the overall aspect ratio of the composition. A line of 15-degree slope descending to the left from this same upper point passes along the shadows on the rocky hills about a third of the way across the composition. A horizontal through the lance intersection point aligns with the ground level of the hills on the far right.

The right margin of the painting may be found by dropping a 45-degree diagonal down from the uppermost left corner of the small dodecagon down to the bottom margin of the painting; this operation thus sets the overall aspect ratio of the composition. A line of 15-degree slope descending to the left from this same upper point passes along the shadows on the rocky hills about a third of the way across the composition. A horizontal through the lance intersection point aligns with the ground level of the hills on the far right. This painting is the property of the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice. This analysis was based on a color-enhanced version of the following image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._George_and_the_Dragon_(Carpaccio)#/media/File:Vittore_carpaccio,_san_giorgio_e_il_drago_01.jpg

This painting is the property of the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice. This analysis was based on a color-enhanced version of the following image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._George_and_the_Dragon_(Carpaccio)#/media/File:Vittore_carpaccio,_san_giorgio_e_il_drago_01.jpg

Limbourg Brothers- Tres Riches Heures of Jean de Berry

Here is Charles Bouleau’s analysis of a miniature from the Tres Riches Heures of Jean de Berry, made by the Limbourg Brothers early in the fifteenth century.

Here is Charles Bouleau’s analysis of a miniature from the Tres Riches Heures of Jean de Berry, made by the Limbourg Brothers early in the fifteenth century. Here Adam and Eve are shown in the Garden of Eden, whose circular perimeter was surely drawn with a compass.

Here Adam and Eve are shown in the Garden of Eden, whose circular perimeter was surely drawn with a compass. More interestingly, Bouleau showed that the height of the Gothic fountain of life in the image could be found by unfolding the diagonal of the square framing the garden’s circular border.

More interestingly, Bouleau showed that the height of the Gothic fountain of life in the image could be found by unfolding the diagonal of the square framing the garden’s circular border. Bouleau also demonstrated that the width of the fountain was set by the intersection of two pentagons inscribed within that circle. In the lower-left of the image, moreover, Adam’s foot locates the corner of the pentagon with the horizontal base.

Bouleau also demonstrated that the width of the fountain was set by the intersection of two pentagons inscribed within that circle. In the lower-left of the image, moreover, Adam’s foot locates the corner of the pentagon with the horizontal base. Bouleau extends that baseline to the right, as shown in green, and then connects it back to the tip of the fountain.

Bouleau extends that baseline to the right, as shown in green, and then connects it back to the tip of the fountain. The intersection of this green diagonal with the circle’s equator, he claims, sets the width of the Gothic portal through which the first couple exit, while the blue diagonal to its top sets the sloping pose of the expelled Eve.

The intersection of this green diagonal with the circle’s equator, he claims, sets the width of the Gothic portal through which the first couple exit, while the blue diagonal to its top sets the sloping pose of the expelled Eve. This page is folio 25v of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, which is MS 65 from the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France. This particular image is from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Tr%C3%A8s_Riches_Heures_du_Duc_de_Berry#/media/File:Folio_25v_-_The_Garden_of_Eden.jpg

This page is folio 25v of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, which is MS 65 from the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France. This particular image is from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Tr%C3%A8s_Riches_Heures_du_Duc_de_Berry#/media/File:Folio_25v_-_The_Garden_of_Eden.jpg

Piero di Cosimo- The Visitation

Here is the Visitation scene painted by Piero di Cosimo.

Here is the Visitation scene painted by Piero di Cosimo. The inner field of the painting is a perfect square, flanked by narrow strips on the bottom and sides. The center of the square locates the clasping hands of the Virgin and Elizabeth.

The inner field of the painting is a perfect square, flanked by narrow strips on the bottom and sides. The center of the square locates the clasping hands of the Virgin and Elizabeth. The center of the square also defines a level, identified here with the orange horizontal, that describes the edge of the architectural platforms on which the small figures in the middle ground stand. From the ends of that horizontal, orange lines of 30-degree slope are now launched.

The center of the square also defines a level, identified here with the orange horizontal, that describes the edge of the architectural platforms on which the small figures in the middle ground stand. From the ends of that horizontal, orange lines of 30-degree slope are now launched. Then, from the points where those orange lines intersect the top of the panel, yellow verticals descend, which frame a yellow circle, in which a yellow square can be inscribed in a quadrature operation. Note that the bottom facet of the square aligns with the back of the platform on which the Virgin and Elizabeth stand.

Then, from the points where those orange lines intersect the top of the panel, yellow verticals descend, which frame a yellow circle, in which a yellow square can be inscribed in a quadrature operation. Note that the bottom facet of the square aligns with the back of the platform on which the Virgin and Elizabeth stand. The front of the platform corresponds to the bottom tip of a green equilateral triangle whose baseline corresponds to the equator of the square. A similar triangle above this equator helps to locate the heads of the two women as they lean towards each other, with their wimples sloped at 60 degrees from the horizontal. Their heads and the Virgin’s halo fit into the almond-shaped figure that circumscribes the paired triangles. One odd detail about this painting is that the horizon line of the seascape in the deep background between the women is not actually horizontal. Instead, it falls gently from left to right.

The front of the platform corresponds to the bottom tip of a green equilateral triangle whose baseline corresponds to the equator of the square. A similar triangle above this equator helps to locate the heads of the two women as they lean towards each other, with their wimples sloped at 60 degrees from the horizontal. Their heads and the Virgin’s halo fit into the almond-shaped figure that circumscribes the paired triangles. One odd detail about this painting is that the horizon line of the seascape in the deep background between the women is not actually horizontal. Instead, it falls gently from left to right. It is tempting to imagine that this might have been because the artist connected the wrong lines in his geometrical armature. Here, blue lines of 30-degree slope depart from the equator of the panel, within the red frame, and one can find the skewed horizon line quite precisely by connecting the point at left where the rising blue line intersects the yellow vertical with the point at right where the falling blue line intersects the side of the green triangle.

It is tempting to imagine that this might have been because the artist connected the wrong lines in his geometrical armature. Here, blue lines of 30-degree slope depart from the equator of the panel, within the red frame, and one can find the skewed horizon line quite precisely by connecting the point at left where the rising blue line intersects the yellow vertical with the point at right where the falling blue line intersects the side of the green triangle. This painting is the property of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Visitation_(Piero_di_Cosimo)#/media/File:Piero_di_cosimo,_vistazione_small.jpg That image has now been superseded by: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Visitation_(Piero_di_Cosimo)#/media/File:Piero_di_Cosimo_023.jpg

This painting is the property of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. This analysis was based on the image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Visitation_(Piero_di_Cosimo)#/media/File:Piero_di_cosimo,_vistazione_small.jpg That image has now been superseded by: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Visitation_(Piero_di_Cosimo)#/media/File:Piero_di_Cosimo_023.jpg

Mondrian- Broadway Boogie-Woogie

Here is the Broadway Boogie-Woogie by Piet Mondrian.

Here is the Broadway Boogie-Woogie by Piet Mondrian.

Charles Bouleau claimed that Mondrian used such armatures governed by the Golden Ratio to define his compositions. Unfortunately, his demonstration of this principle was far less plausible than many of his other analyses, so we will be walking step-by-step through this connection.

Here is the unfolded half-diagonal section of the square painting, so as to form a Golden Rectangle.

The successively smaller squares constructed along this rectangle’s diagonal locate the heights of the red lines shown at left, each of which forms the top margin for one of Mondrian's streetlike color strips.

The successively smaller squares constructed along this rectangle’s diagonal locate the heights of the red lines shown at left, each of which forms the top margin for one of Mondrian's streetlike color strips. The orange rectangle at upper left is actually a Golden Rectangle in terms of proportion; its bottom edge aligns with the lower red horizontal, and its right margin defines one of the main verticals in the painting.

The orange rectangle at upper left is actually a Golden Rectangle in terms of proportion; its bottom edge aligns with the lower red horizontal, and its right margin defines one of the main verticals in the painting. An arc swung up from the lower right corner of the painting through the intersection of this vertical and the second horizontal rises to height .441, a level through which is a green horizontal, which again forms the top edge of a color strip. The green rectangle and square above this level locate the right edges of two vertical color strips.

An arc swung up from the lower right corner of the painting through the intersection of this vertical and the second horizontal rises to height .441, a level through which is a green horizontal, which again forms the top edge of a color strip. The green rectangle and square above this level locate the right edges of two vertical color strips. The blue square and rectangle within the green square serve a similar function on a smaller scale.

The blue square and rectangle within the green square serve a similar function on a smaller scale. A few more constructions based on diagonals locate features such as the large blue rectangle in the painting’s upper right quadrant, and the horizontal color strip immediately above it, at height .842. With its insistently rectilinear articulation, Broadway Boogie Woogie might seem to represent the very antithesis of compass-based circular thinking. To the extent that its proportions were based on those of the Golden Rectangle, though, it contains circles below its surface.

A few more constructions based on diagonals locate features such as the large blue rectangle in the painting’s upper right quadrant, and the horizontal color strip immediately above it, at height .842. With its insistently rectilinear articulation, Broadway Boogie Woogie might seem to represent the very antithesis of compass-based circular thinking. To the extent that its proportions were based on those of the Golden Rectangle, though, it contains circles below its surface. This painting is the property of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This analysis was based on the image: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78682

This painting is the property of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This analysis was based on the image: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78682

Baltimore

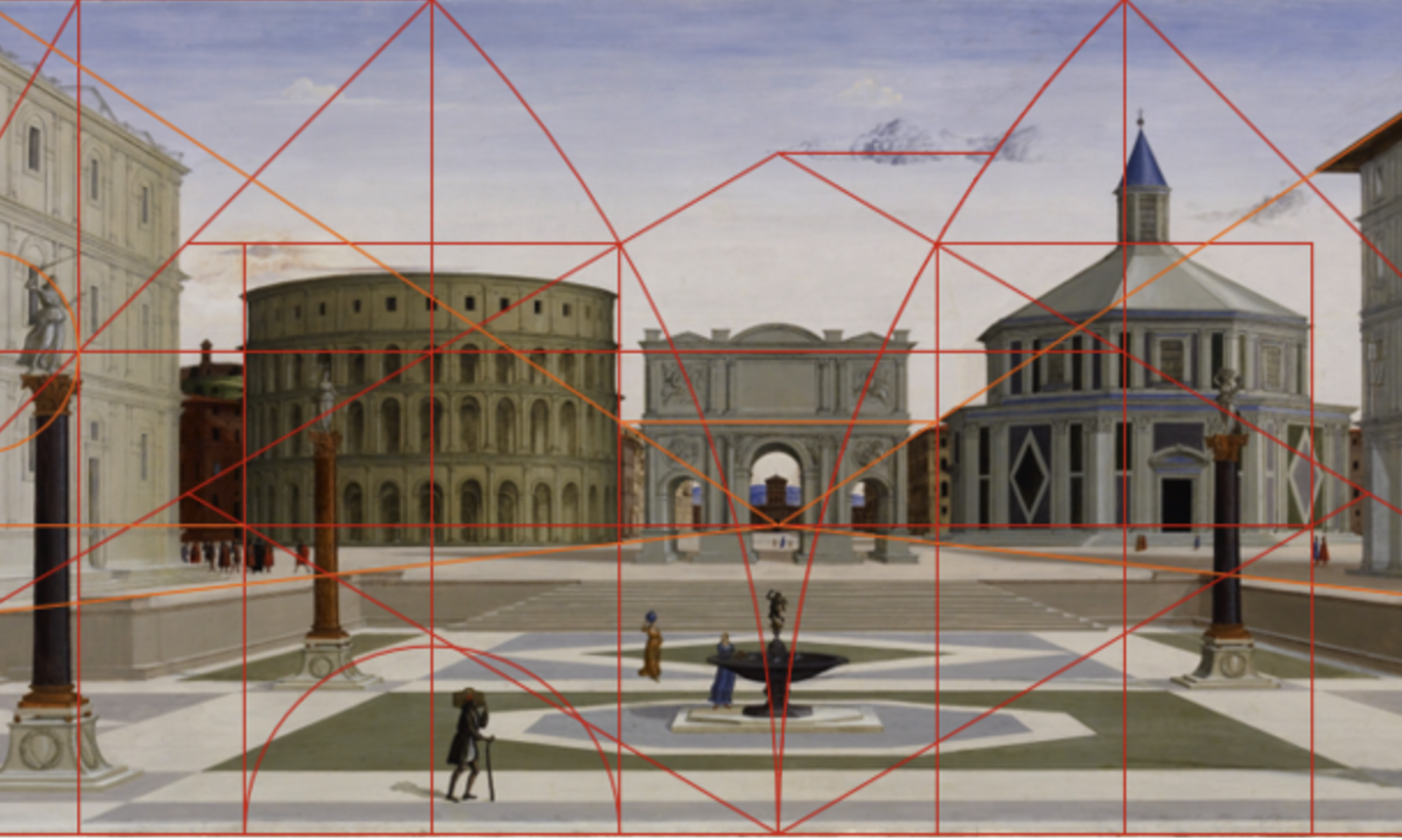

Here is an anonymous Italian Renaissance painting of an ideal city painting now preserved at the Walters Gallery in Baltimore. Its width is considerably greater than its height.

Here is an anonymous Italian Renaissance painting of an ideal city painting now preserved at the Walters Gallery in Baltimore. Its width is considerably greater than its height. More specifically, its width is 2.828 times its height, or two times the square root of two. This can be seen by unfolding the diagonals of two squares set on its outer edges. Note that the right margin of the left square aligns with the central axis of the amphitheater in the distance.

More specifically, its width is 2.828 times its height, or two times the square root of two. This can be seen by unfolding the diagonals of two squares set on its outer edges. Note that the right margin of the left square aligns with the central axis of the amphitheater in the distance. Several key elements in the painting can be found by tracing lines of 30-degree and 60-degree slope upward from its outer lower corners. The right margin of the amphitheater aligns with the vertical where the 30-degree line cuts the left arc, and the left margin can be found by reflection. The baptistery at right fits into a nearly equivalent frame, although it is compressed slightly to the right.

Several key elements in the painting can be found by tracing lines of 30-degree and 60-degree slope upward from its outer lower corners. The right margin of the amphitheater aligns with the vertical where the 30-degree line cuts the left arc, and the left margin can be found by reflection. The baptistery at right fits into a nearly equivalent frame, although it is compressed slightly to the right. The front corners of the palaces in the foreground can be found by first drawing a yellow horizontal through the point where the 30-degree orange line cuts the axis of the amphitheater, and then drawing yellow verticals through the circled points halfway between the intersections of this horizontal with the 45- and 60-degree lines.

The front corners of the palaces in the foreground can be found by first drawing a yellow horizontal through the point where the 30-degree orange line cuts the axis of the amphitheater, and then drawing yellow verticals through the circled points halfway between the intersections of this horizontal with the 45- and 60-degree lines. The rear corners of the palaces are exactly halfway between the panel margins and its center, as the green verticals indicate, and the green horizon line can be found at the level where the rising green lines of 30-degree slope cut the orange margins of the amphitheater and the baptistery.

The rear corners of the palaces are exactly halfway between the panel margins and its center, as the green verticals indicate, and the green horizon line can be found at the level where the rising green lines of 30-degree slope cut the orange margins of the amphitheater and the baptistery. The top edge of the right-hand palace can be found by running a blue line from the vanishing point to the top of the yellow vertical describing the right-hand palace corner. From the point where this blue line cuts the orange line of 60-degree slope, a blue vertical can be dropped to find the axis of the column in the foreground, and a similar construction also works in the left half of the panel, even though the palace there is shorter.

The top edge of the right-hand palace can be found by running a blue line from the vanishing point to the top of the yellow vertical describing the right-hand palace corner. From the point where this blue line cuts the orange line of 60-degree slope, a blue vertical can be dropped to find the axis of the column in the foreground, and a similar construction also works in the left half of the panel, even though the palace there is shorter. The perspectival lines in the pavement can be found by connecting the vanishing point to already constructed points in the foreground, and a similar scheme located at the front edge of the platforms on which the palaces stand.

The perspectival lines in the pavement can be found by connecting the vanishing point to already constructed points in the foreground, and a similar scheme located at the front edge of the platforms on which the palaces stand. This painting is the property of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. This analysis was based on the image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ideal_City_(painting)#/media/File:Fra_Carnevale_-_The_Ideal_City_-_Walters_37677.jpg

This painting is the property of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. This analysis was based on the image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ideal_City_(painting)#/media/File:Fra_Carnevale_-_The_Ideal_City_-_Walters_37677.jpg

Provisional Investigation of Geometric Proportions in 15th-century Cologne Panel Painting

Author: Robert Bork